When Nigeria’s 36 states line up for the Federation Account Allocation Committee (FAAC) each month, the queue looks the same, but the dynamics behind it are changing. After two decades of oil-linked dependency, some states are finally learning how to earn, not just receive.

The shift is visible in the data. In 2023, Nigeria’s states and the FCT generated ₦2.43 trillion ($3.82 billion), in internally generated revenue (IGR), a 26% rise in naira terms from ₦1.93 trillion ($4.55 billion) in 2022, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

Yet more than half of that total came from only five states: Lagos, Rivers, Ogun, Delta, and Kaduna. The rest remained structurally dependent on FAAC transfers. However, a structural change is ongoing that may alter this dynamic.

Note: The drop in the dollar value of IGR is primarily an effect of the Naira’s devaluation, not a sign that states are generating less revenue in local terms. The comparison demonstrates the severe impact of currency volatility on Nigeria’s economic indicators when measured against a stable international currency like the US dollar.

From dependence to design

Policy design separates the top performers.

Lagos, still the model, built its tax base by automating revenue collection, digitising land registries, and integrating MDAs through its Treasury Single Account (TSA). The state’s ₦815.9 billion IGR in 2023 — one-third of the national total — reflects 20 years of institutional muscle built around technology and compliance.

Kaduna followed a similar playbook at a smaller scale. Its GIS-based property and land administration system, coupled with a digital tax portal, lifted non-oil revenue and improved budget predictability. The World Bank’s State Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Programme repeatedly ranks Kaduna among the top five performers on fiscal transparency and e-governance adoption.

Then there’s Enugu, an unexpected entrant in the conversation. Long known for its coal-era nostalgia, the state has quietly become a fiscal reform laboratory. Between 2023 and 2024, its IGR leapt from ₦37.6 billion ($59.19 million) to ₦180.5 billion ($122.61 million) — a 4.8× jump — overtaking its federal allocation by roughly ₦30 billion. The driver? Aggressive digitisation of tax collection, free right-of-way for broadband infrastructure, and a deliberate shift toward capital-heavy budgeting.

Enugu’s fiscal experiment is now a reference point for mid-tier economies trying to leapfrog through technology,” Ezeh says. “We’re not competing with other Nigerian states; we’re benchmarking against cities across the globe.”

Ogun, by contrast, has focused on industrial corridors, deploying PPP road projects and automated land charges to make its manufacturing base pay for itself. Edo is rewiring its grid and is among the first to set up a state power regulator under the Electricity Act 2023.

Each of these examples underscores the same logic: fiscal resilience is no longer just about mineral endowment or size. It’s about governance bandwidth — the ability to use data, digital infrastructure, and credible budgeting to keep the economy moving even when Abuja doesn’t.

The anatomy of fiscal innovation

Across reform-minded states, three patterns are emerging:

1. Revenue systems are going digital.

Some states like Ogun and Enugu now use e-receipts, automated remittance tracking, and bank-integrated payment gateways to plug leakages. The move not only lifts yield but builds financial visibility, allowing banks to underwrite state obligations with clearer data trails.

2. Infrastructure is being reframed as fiscal policy

Kaduna’s investment in roads and logistics, Ogun’s new industrial corridors, and Enugu’s zero-cost broadband access all signal a recognition that capital expenditure (capex) is moving from development projects to revenue-enabling. Businesses pay taxes where they can move goods, connect, and transact efficiently.

3. Budgets are reweighted toward capital spend

According to BudgIT, at least 14 states allocated more than 45 % of their 2024 budgets to capital projects — a sharp reversal from years of recurrent-dominated spending. Enugu earmarked ₦207 billion ($140.61 million) for capex, Kaduna ₦180 billion ($122.27 million), and Lagos over ₦500 billion ($339.64 million). The open question: can execution match ambition?

The money behind the momentum

IGR growth doesn’t always mean liquidity or diversified revenue streams. Some states, notably Rivers and Delta, still rely heavily on oil-linked corporate taxes. Others, like Ekiti or Taraba, saw modest revenue growth but poor capital execution, signalling limited absorptive capacity.

By contrast, Enugu’s revenue surge was tied to automation and compliance rather than one-off windfalls. Kaduna’s success was driven by tightening land administration and widening the tax net to the informal sector. Lagos remains the only state where tax receipts alone can cover operating expenses — but its playbook is now being localised elsewhere.

The distinction matters: not all IGR is equal. Revenue based on systematised collections can be securitised or used to anchor infrastructure bonds; revenue dependent on political goodwill or extractive royalties is much more difficult.

Subnationals as a new credit class

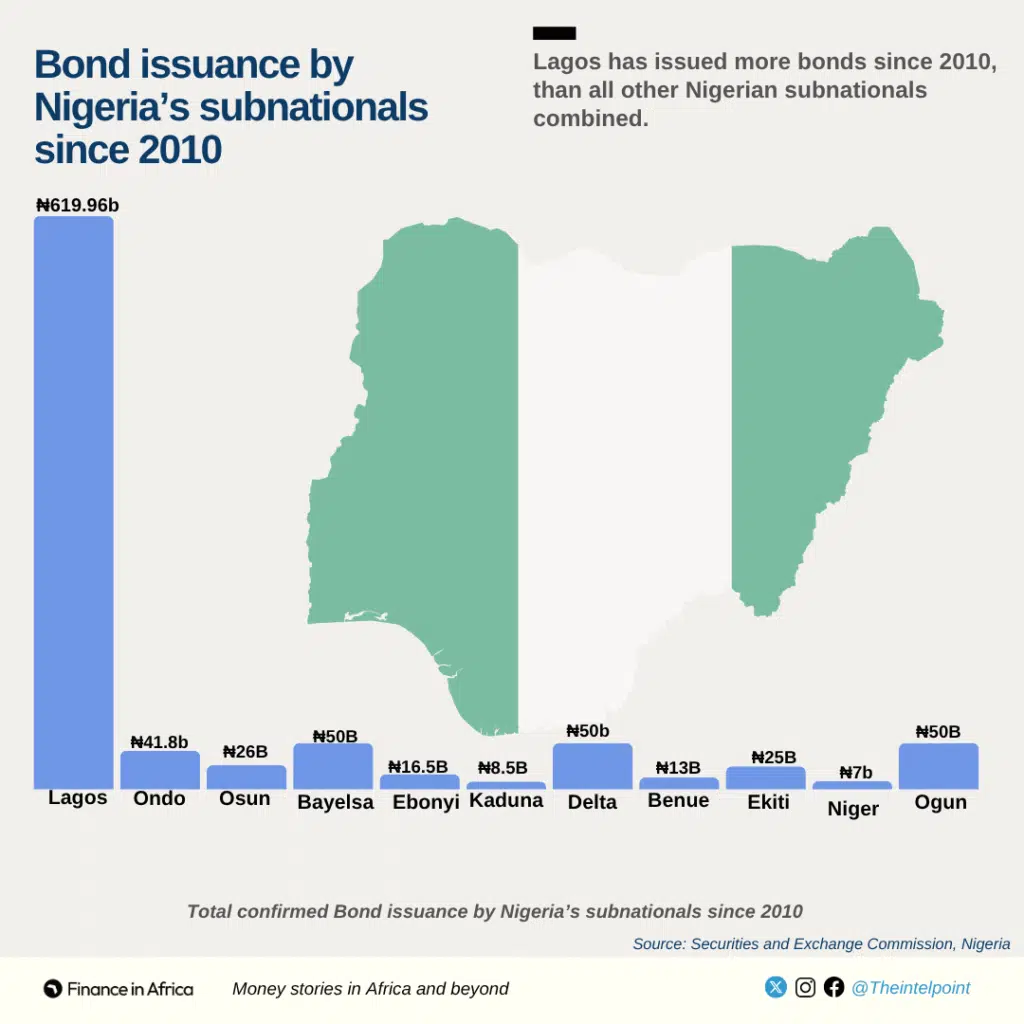

The fiscal re-engineering of Nigerian states is already influencing credit markets. Since 2020, subnational bond issuances have regained traction — with Lagos, Ondo, and Osun leading. Enugu and Kaduna could also follow this route if reforms continue.

But investors are watching for consistency. Many states still back-load their capex execution — spending over 60 % of annual allocations in the last quarter, often for political or procurement reasons. That volatility makes year-on-year comparisons difficult and raises questions about institutional maturity.

The emerging subnational hierarchy is no longer North vs South, or oil vs non-oil. We can narrow it down to execution vs aspiration.

- Lagos remains the standard for systemised fiscal capacity.

- Kaduna shows how governance reform scales in a mid-tier economy.

- Enugu demonstrates the velocity possible when digital infrastructure becomes fiscal infrastructure.

The challenge for the rest is replication under constraint: weak institutions, limited tax data, and political turnover that resets reforms every four years.

Still, the trajectory is encouraging. As federal transfers stagnate and debt service ratios rise, subnational governments are discovering what Lagos learned two decades ago — that survival depends on owning the pipes through which money flows.

Why this matters

Nigeria’s subnational transformation is both a credit-risk story and an investment map. States that can show sustained digital revenue growth, high capex execution, and fiscal transparency will attract concessional funding and structured credit. Those that can’t will increasingly price themselves out of capital markets.

The next frontier is interoperability — linking state treasury systems with banking APIs, payments infrastructure, and federal oversight frameworks. When that happens, Nigeria’s fiscal geography will finally start to look like its demography: decentralised, data-driven, and competitive.

Editor’s note: The dollar values in this story were calculated using the annual average exchange rates for each year, which were:

- 2022: ₦423.72 to $1 USD

- 2023: ₦635.24 to $1 USD

- 2024: ₦1,472.15 to $1 USD (as derived from CEIC and other sources)

Due to high Naira volatility, these conversions primarily reflect currency devaluation, not changes in local revenue generation.