The European Union has lifted its high-risk designation for six African countries, after years in which the listing reshaped how capital moved in and out of their economies.

Between 2022 and 2023, the European Union placed Nigeria, South Africa, Burkina Faso, Mali, Mozambique, and Tanzania on its high-risk financial list, citing serious weaknesses in their frameworks for combating money laundering and terrorist financing.

Although added at different times, by 2023, all six were operating under the same intensified scrutiny from European regulators and banks. The European Commission’s warning that these deficiencies threatened the EU’s financial system quickly influenced global market behavior.

Transactions involving listed jurisdictions ceased to be routine. European banks applied enhanced due diligence, compliance timelines lengthened, costs increased, and cross-border financing became more cautious, conditional, and risk-averse.

For countries already navigating fragile capital inflows, the listings translated regulatory judgments into real economic constraints.

Nigeria

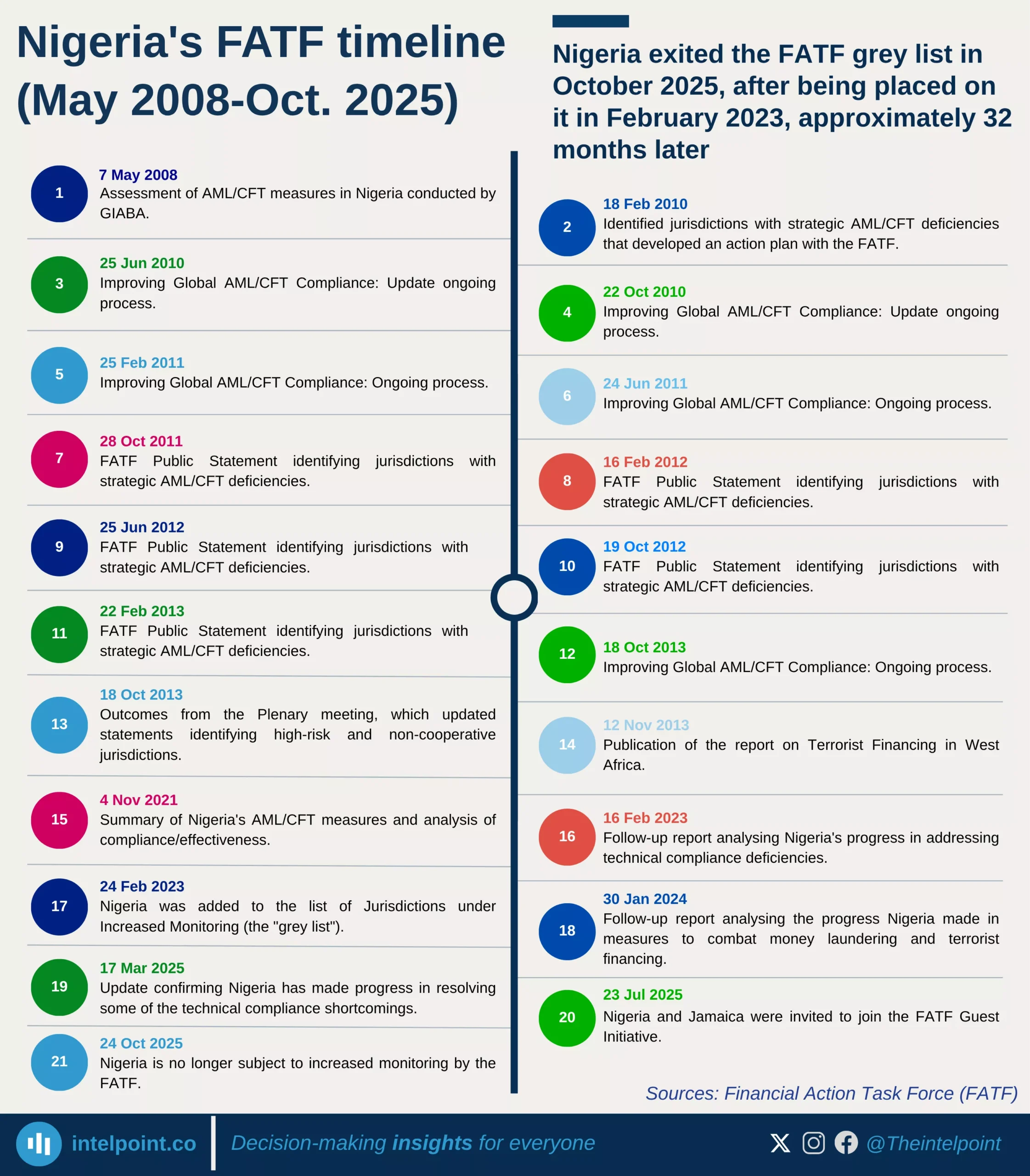

Nigeria’s placement on the EU’s high-risk third-country list followed its inclusion on the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) grey list in February 2023.

FATF identified persistent weaknesses in Nigeria’s anti-money-laundering and counter-terrorism financing (AML/CFT) regime, including ineffective supervision, limited transparency, weak inter-agency coordination, and low enforcement outcomes for serious financial crimes.

Under EU law, FATF grey-listing automatically triggers a high-risk designation, requiring European financial institutions to apply enhanced due diligence to transactions involving the affected jurisdiction.

The economic consequences were swift and far-reaching. Global investors like sovereign wealth funds, private equity firms, and portfolio managers, reassessed Nigeria’s regulatory and governance risk profile.

Foreign direct investment declined sharply, falling to just $29.8 million in the second quarter of 2024, a year-on-year drop of approximately 75 percent. By the first quarter of 2025, FDI remained roughly 70 percent lower than the preceding quarter, as investors increasingly favoured short-term portfolio exposure over long-term, capital-intensive commitments in sectors such as energy, infrastructure, and manufacturing.

The Central Bank of Nigeria later estimated that FATF grey-listing and its spillover effects contributed to losses exceeding $30 billion in potential investment inflows.

Financial operations were equally affected. Enhanced due diligence requirements slowed cross-border transfers, increased transaction costs, delayed letters of credit, and constrained access to correspondent banking services.

Businesses, fintechs, freelancers, and households experienced longer processing times and higher fees for international payments, while exporters and importers faced heightened uncertainty in accessing foreign exchange.

At the sovereign level, AML/CFT deficiencies fed into credit-risk assessments, prompting stricter lending conditions, higher risk premiums, and reduced access to external financing.

South Africa

South Africa’s regulatory path followed a familiar pattern. In February 2023, FATF gray-listed the country for 22 deficiencies in its AML/CFT framework, prompting the EU to classify it as a high-risk third country in August under Article 9(1) of Directive (EU) 2015/849.

The designation required EU financial institutions to apply enhanced due diligence to South African transactions, including additional documentation, continuous monitoring, and senior management approval.

South Africa’s National Treasury acknowledged that these measures introduced friction into financial flows, slowing cross-border payments, complicating trade finance, and increasing compliance costs for banks and businesses engaging European counterparties.

Major South African banks, which already had cost-to-income ratios between 54–59 %, above the regional average of ~40 %, faced additional operational pressures as they invested heavily in compliance systems, staff, and reporting processes. Rising interest rates provided some relief, with Standard Bank projecting a 15 % rise and FirstRand a 10 % rise in net interest income year-on-year.

Although South Africa did not record investment losses as sharply quantified as Nigeria’s, the reputational impact was material. International banks and investors tightened internal risk thresholds and showed reduced appetite for long-term investments, particularly in infrastructure and manufacturing.

Globally, FATF graylisting is associated with 7.6 % decline in capital inflows and 3 % drop in foreign direct investment, illustrating the broader pressures on banks and financial markets.

Heightened scrutiny by foreign regulators and correspondent banks continued through 2023–2025, sustaining operational friction in cross-border transactions and trade finance.

Reflecting on the operational burden of grey‑listing, Jee‑A van der Linde, senior economist at Oxford Economics in Cape Town, noted that being placed on the FATF grey list made it “much harder” for South Africa to attract foreign capital and added to negative sentiment about the country’s financial system.

Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso was placed on the EU’s high-risk third-country list in March 2022 following its FATF grey-listing for strategic AML/CFT deficiencies.

FATF identified weaknesses in financial supervision, transparency of beneficial ownership, and enforcement capacity across both financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses.

As with other jurisdictions, EU rules automatically imposed enhanced due diligence requirements on transactions involving Burkinabé entities.

The economic impact was significant. IMF research indicates that FATF grey-listed countries experience average capital inflow declines of approximately 7.6 percent of GDP.

Applying this pattern, estimates suggest Burkina Faso may have lost over $1.5 billion during the high-risk period, including approximately $609 million in foreign direct investment and $589 million in portfolio investment.

Enhanced compliance requirements increased documentation burdens, slowed settlements, and raised transaction costs, reinforcing investor caution and reducing long-term capital commitments.

Impact on other African economies

Following other jurisdictions, Mali, Tanzania, and Mozambique also faced comparable challenges under FATF and EU high-risk designations.

Mali was grey-listed due to deficiencies in financial oversight, ownership transparency, supervision of non-financial sectors, and enforcement effectiveness, while Tanzania and Mozambique were flagged for weak supervision, limited financial intelligence capacity, and enforcement gaps, as well as insufficient investigation and prosecution of financial crimes in Tanzania.

Using the same IMF benchmark introduced for Burkina Faso, estimates suggest Mali may have lost approximately $1.59 billion, Mozambique around $1.57 billion, and while Tanzania-specific figures are not precisely quantified, similar reductions in capital inflows are likely.

These designations also increased operational frictions as payments slowed, trade finance instruments such as letters of credit faced delays, and fintechs and remittance providers experienced higher compliance costs.

Experts highlight these effects as a direct consequence of regulatory weaknesses. For instance, Vincent Gaudel, financial crime compliance expert at LexisNexis Risk Solutions, noted that grey-listing “increases transaction costs and slows correspondent banking flows, affecting trade and investment.”

Similarly, Bastian Teichgreeber, Chief Investment Officer at Prescient Investment Management, explained that such listings “raise perceived risk premiums for investors, constraining capital allocation and dampening long-term investment sentiment.”

In line with regional reports, these impacts demonstrate how structural AML/CFT gaps translate into constrained investment, elevated risk premiums, and higher costs for cross-border transactions, reinforcing a broader trend of economic strain across the affected African economies.

What the removal means for African economies

With the EU’s removal of Burkina Faso, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, South Africa, and Tanzania from its high-risk third-country list, effective January 29, 2026, and the FATF delisting preceding it, the economic landscape for these countries is set to improve significantly.

These updates came after all six countries completed action plans to address strategic AML/CFT deficiencies, strengthening financial supervision, enhancing intelligence sharing, and improving enforcement of anti-money-laundering regulations.

Experts emphasize that the delisting is more than symbolic as it directly affects how banks, investors, and businesses operate across borders. With enhanced due diligence no longer automatically applied, transaction delays, higher compliance costs, and documentation burdens are expected to decline.

Hafsat Abubakar Bakari, CEO of the Nigerian Financial Intelligence Unit, noted that Nigeria’s removal should “ease compliance burdens, improve cross-border financial flows, and boost Nigeria’s attractiveness for trade, investment, and partnerships with EU member states.”

Financial analysts also see this regulatory improvement as a confidence signal to international markets. Frank Blackmore, lead economist at KPMG South Africa, explains that reduced compliance drag can reignite trade and investment momentum with Europe, lower funding costs, and expand access to capital for both public and private sector projects.

Furthermore, delisting is expected to revive correspondent banking relationships, encourage investment, and improve terms for international trade, particularly in sectors like infrastructure, energy, and manufacturing.

A real-world precedent is the Philippines’ exit from the FATF grey list in February 2025, which led to faster, less costly cross-border transactions and an increase in foreign business registrations and investment inflows.

Civil society voices also highlight the broader benefits of delisting. The Africa Network for Environment and Economic Justice (ANEEJ) describes it as a milestone that can enhance investor confidence and economic credibility, while urging continued reforms to maintain transparency and guard against illicit financial flows.

In practice, these changes mean shorter processing times for international payments, fewer mandatory reporting layers, and lower perceived AML/CFT risk, which collectively reduce the cost of doing business internationally.

For exporters, importers, banks, and investors, this translates into improved trade terms, greater access to finance, and stronger capital inflows, offering the potential for more robust economic growth across the region.

At the same time, South Africa’s National Treasury has cautioned that delisting does not mean all challenges are resolved. The National Treasury emphasized that governments and private sector actors must avoid complacency, continue improving enforcement, maintain strong institutions, and ensure that reforms are sustainable, warning that the next FATF evaluations will assess whether these improvements are effectively implemented.