Across West Africa, food inflation is easing — at least on paper. In reality, underlying pressures remain firmly in place, constraining price relief for households and businesses operating along the food value chain.

Weak logistics infrastructure, unreliable power supply, and widespread post-harvest losses continue to distort food supply, push up prices and complicate decision-making for operators — particularly in Nigeria, the region’s largest economy.

In this interview with Finance in Africa, Kofi Abunu, Managing Director of Food Concepts, parent company of Chicken Republic, and one of West Africa’s leading quick service restaurant (QSR) groups, breaks down the structural drivers behind sticky food inflation.

He explains how farm-to-market inefficiencies are reshaping pricing decisions, squeezing margins and forcing operators to become self-reliant.

What are the biggest challenges operators and businesses in the food supply chain network in West Africa are currently facing?

One of the biggest challenges is what industry players call farm-to-market inefficiencies. Nigeria is a prime example. Major food-producing states such as Plateau, Benue, Oyo and Ogun lack feeder roads — the smaller roads that connect rural communities to major highways.

As a result, farm produce does not reach the right markets on time. When it finally does, it often arrives bruised or partially spoiled because the available roads are often in bad shape. In an industry where consistency and food safety are everything, this leads to high rejection rates.

The second major challenge is energy, and the problem is threefold. First is unreliable power supply, which forces operators to rely on diesel- or fuel-powered generators to preserve perishable food and meat, driving up costs.

These problems are made worse by rising energy tariffs, which have increased steadily since 2022. Then there are multi-city levies and checkpoints. Exporters are hit particularly hard, facing numerous checkpoints and informal payments when moving goods across borders. Producers cannot absorb these costs, so they pass them on to the end user, pushing food prices higher.

Nigerian operators also face the added burden of widespread insecurity. Too often we read reports of farmers being attacked or chased off their land, and those who continue farming often have to provide their own security, further increasing the cost of doing business.

Q. What are the major economic costs of these challenges?

In economic terms, these challenges often result in significant food losses and price escalation. Over the years, Nigeria has reportedly lost billions of naira annually to post-harvest losses caused by weak logistics infrastructure. Take tomatoes as an example.

As a highly perishable crop, excessive shaking during transportation from farm to market can cause substantial damage, with losses sometimes reaching 50% of the harvest. By the time the produce reaches consumers, prices can triple — not because of scarcity at the farm level, but due to transport delays, high fuel costs and inefficiencies along the supply chain.

For us as QSR operators, volatility in input prices makes long-term planning extremely difficult, from supplier contracts to working capital. Take vegetables, for example. The off-season typically runs from April through July, and during that period prices can jump by 40 to 60%.

That shouldn’t be the case. With the right infrastructure, not just for transport, but for storage, price increases could be contained to maybe 10%, which would allow businesses like ours to plan better.

Instead, we face both scarcity and sharp price hikes, and as a fast-food business, those costs are passed straight on to the customer. In simple terms, Nigerians are paying for food multiple times over — first to grow it, and then again to replace what is lost.

Q. How have these deficits affected food inflation in the region?

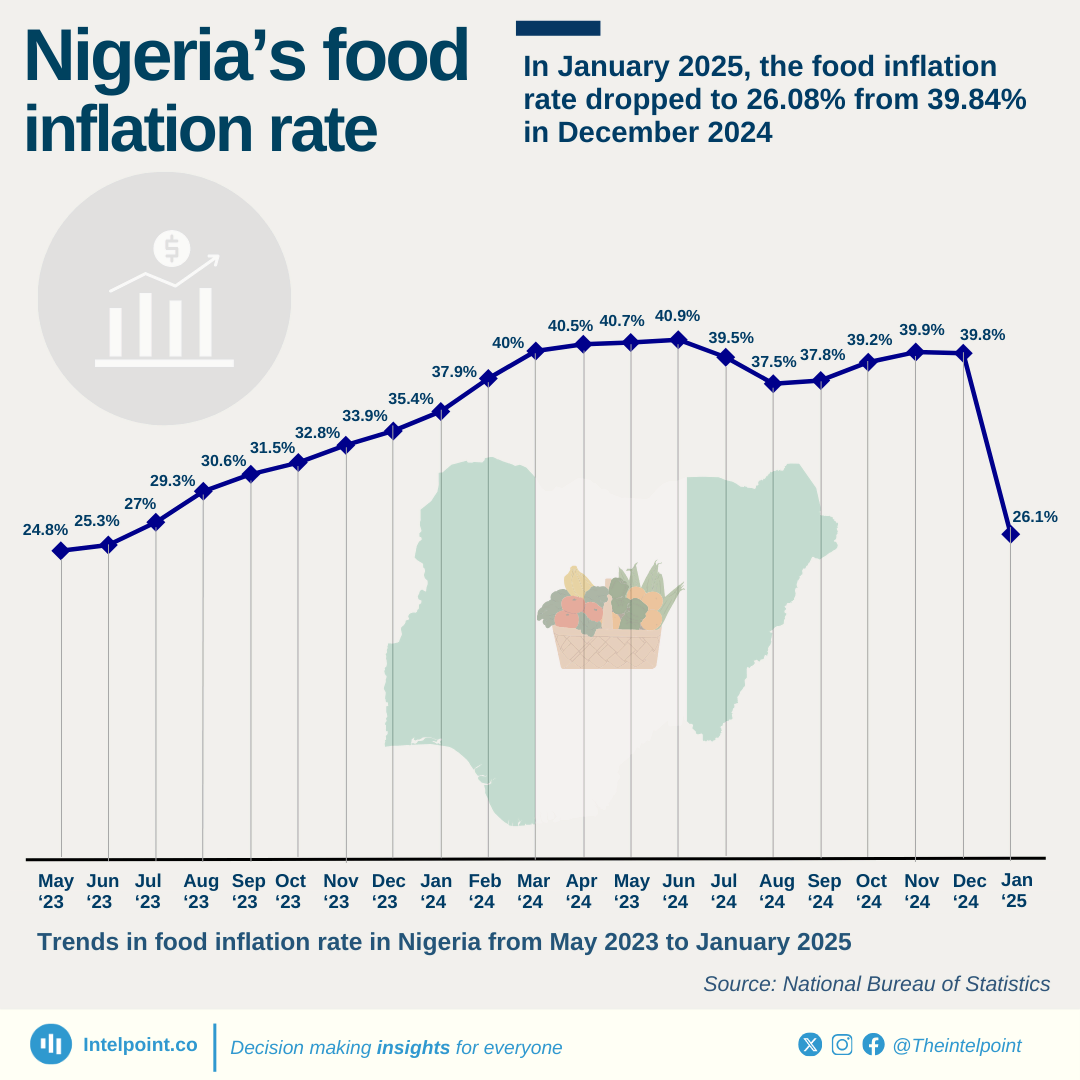

Using Nigeria, because of its importance to the West African economy, we see that food inflation is not driven by demand alone. It is structural. As I mentioned earlier, poor roads, congestion and the lack of cold storage reduce usable supply, so prices rise even during harvest season.

Energy costs are another major factor, especially diesel. Operators are constantly trying to improve energy efficiency, but instead of reliable grid power and predictable meter bills, diesel costs are embedded across storage, processing and distribution — and ultimately in food prices.

For restaurants and QSRs, this means frequent changes in input prices, forcing difficult decisions around menu pricing and portion control. That is why food inflation remains sticky and price relief is slow, even when production improves.

In theory, prices should fall in peak season, but in Nigeria and across Africa, once prices go up, they tend to stay there. Businesses absorb part of the shock. When food inflation hit 39% in 2024, many raised prices by just 5–10%, who’s covering the 29%?

The company’s taking the hit. So as soon as harvest improves, we maintain the price instead of reducing it by that 10% increase. We maintain it because we’ve got to recover what we lost.

In 2025, headline inflation, which is largely driven by food price growth, eased across Africa. What is changing, and how is this shift affecting the prices of consumer-ready food?

After Nigeria rebased its inflation data, headline inflation fell from about 39% to 14% as of November 2025. For QSRs, this translated into a pause in price increases. It does not mean input costs came down; it just means they are simply no longer rising at the same pace.

With prices stabilising and market conditions improving, QSRs are now looking at how to pass some of that relief on to customers, whether through more affordable pricing or targeted promotions, so they can win back customers lost during the hyperinflationary period.

If the current disinflation trend persists, businesses will be able to plan for the long term rather than operate quarter to quarter. Investments will also increase because you can take loans knowing where the funding will be used and how returns will be generated.

When uncertainty dominates, businesses become hesitant. In that situation, interest rates are not the main concern; the real question is whether the loan can be repaid at all.

Q. How are operators in the sector scaling amidst these challenges?

In other West African markets, scaling is a bit simpler. In Ghana, for example, it is not as difficult, largely because of its smaller population and long-standing dependence on agriculture, which has allowed the country to build the infrastructure needed to support production and supply. The same applies to Côte d’Ivoire.

In Nigeria, however, the pressures are far more pronounced. Scaling now requires deliberate self-reliance. Operators can no longer function as restaurants alone; they increasingly have to become their own logistics and supply-chain companies.

At Food Concepts, growth from a single-digit outlet base to 300 nationwide has been driven by central and regional kitchen hubs, as well as distribution hubs, to ensure consistency and reduce reliance on fragmented sourcing.

We also use direct supply partnerships and cluster-based expansion, which helps cut logistics costs. In addition, 99% of our ingredients are sourced locally, reducing the impact of foreign-exchange volatility on our balance sheet.

Q. What support have African governments provided over the years?

Over the years, we’ve seen many good policies from governments across West Africa, but execution remains slow. In Nigeria, there have been central bank financing interventions and plans to support farming and agro-processing, yet many of these initiatives have stalled.

That said, some progress has been made, particularly around boosting local production through import substitution for products such as poultry. Ghana has not taken this approach, which is why locally produced chicken there is often more expensive than imported alternatives.

There are also ongoing discussions around road and port reforms, especially in Apapa and other major logistics corridors, but the gaps remain. The core issue is still helping farmers get the right infrastructure to move produce to consumers — especially cold-chain infrastructure and policy consistency.

It may sound repetitive, but it is the simplest thing. Coordination across agencies is also critical. Customs cannot be saying one thing, NAFDAC another, and the Ministry of Environment something else, all on the same issue. So, progress has been made, but not at a scale needed to materially lower food costs.

Q. Where do private investments come in?

Private investment is non-negotiable. I think the areas where private capital would have the most impact now are food processing facilities, such as cold storage infrastructures, as they can help to reduce perishability and support price stability. I’ve seen private companies invest heavily in warehousing, fleet management and cold-chain logistics, and the results have been impressive.

What investors need is government support to make sure these investments generate good returns. The government’s role should be to enable, de-risk and regulate fairly.

However, current macroeconomic conditions continue constraining private investment, so it comes back to creating a conducive environment where operators and investors can reap the benefits of these commitments.