When U.S. President Donald Trump first targeted China in early 2017, few could have predicted the far-reaching consequences of his aggressive trade stance.

What began as a campaign promise to bring manufacturing back to American soil quickly snowballed into a full-blown trade war, shaking global markets and triggering contractions across continents.

By 2019, after nearly two years of tit-for-tat tariffs between the world’s two largest economies—affecting hundreds of billions of dollars in trade—the global economy contracted by 0.8%, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Fast forward to 2025, and Trump’s return to the White House has reignited tensions.

The World Trade Organisation now warns that the renewed trade war could wipe out 7% of global growth.

In a sweeping protectionist move, Washington initially imposed broad-based tariffs on nearly all of its trading partners, including over 45 African nations—a move he has now placed on hold for the next three months.

However, China has not been exempted and continues to face tariffs as high as 145% on its exports to the U.S. Beijing has responded by slapping a 125% tariff on U.S. exports.

The escalating tensions have sent stock markets convulsing, stoked recession fears, and shaken investor confidence, raising alarms across both advanced and emerging economies.

Though Africa is not a direct combatant in this trade war, the fallout is real and threatening.

From falling commodity prices and rising debt service risks to uncertainty over AGOA and capital market pressure, African economies are once again vulnerable to a conflict they did not start—but may not escape.

Africa’s economic ties: a risky balancing act

Trade relations between Africa and China have grown steadily in recent years, with China now firmly established as sub-Saharan Africa’s largest trading partner.

Over the past two decades, bilateral trade has surged from $11.67 billion in 2000 to $296 billion in 2024, reflecting a growing economic partnership driven largely by China’s appetite for raw materials.

That momentum shows no sign of slowing.

Since December 2024, China has removed tariffs on exports from 33 of Africa’s least developed countries—broadening its trade footprint and reinforcing its influence across the continent.

Major resource exporters such as South Africa, Angola, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Zambia have reaped the benefits, supplying China with crude oil, cobalt, copper, and iron ore.

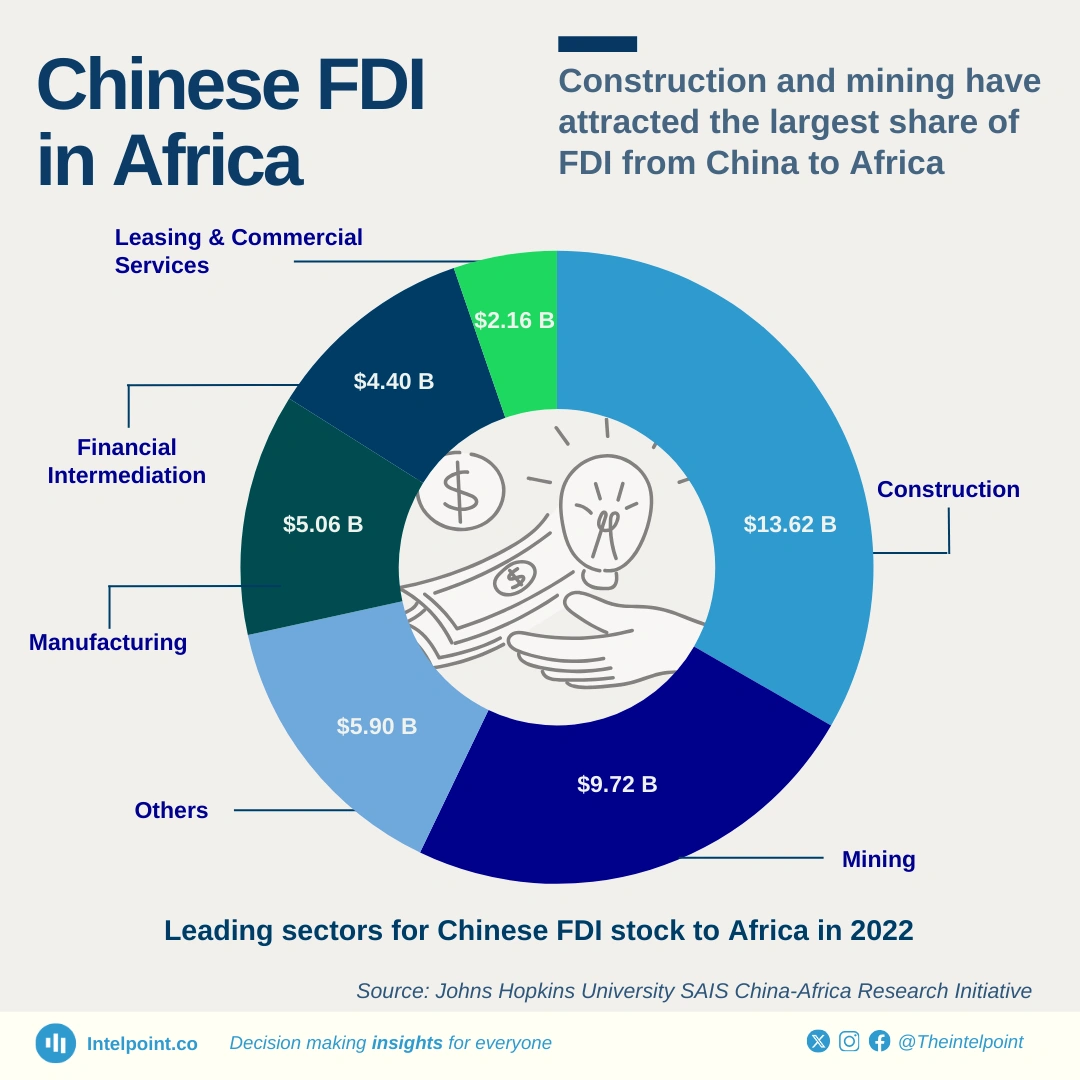

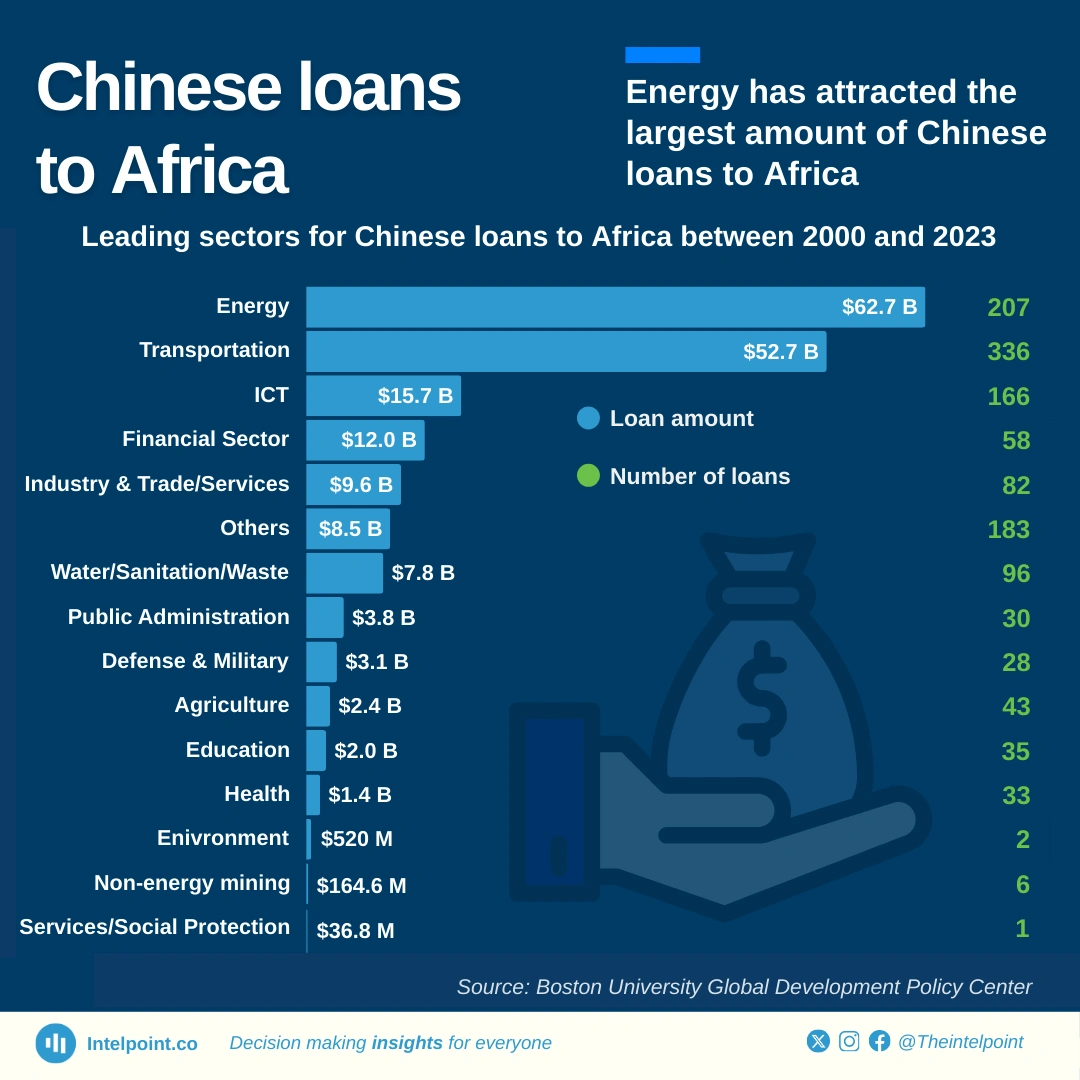

At the same time, Chinese-backed infrastructure projects and development loans have played a central role in shaping long-term national growth strategies.

On the other hand, the U.S. remains a significant trade partner to Africa, with total trade reaching $80 billion in 2024.

A key enabler of this relationship is the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which grants duty-free access to the U.S. market for thousands of African goods.

AGOA has played a central role in boosting non-oil exports in countries like Kenya, Ghana, Ethiopia, and Lesotho, where nearly 70% of exports benefit from the agreement.

However, the current trade war has cast a long shadow over these relationships.

For resource-rich African nations that export minerals and crude oil to China, a weakening Chinese economy, hit hard by retaliatory tariffs, could mean reduced demand and falling commodity prices.

A recent report by Afreximbank warns that Beijing may also reassess its overseas investment strategy, including key Belt and Road Initiative commitments, as growth slows at home.

This shift could tighten the flow of Chinese capital into Africa, especially for countries that have come to depend on it for infrastructure development. The result may be stalled projects and growing fiscal pressure in economies already burdened by debt.

Meanwhile, the future of AGOA remains uncertain. Since former President Trump’s “Liberation Day” announcement, there has been speculation that the programme has either been scrapped, suspended, or is under review.

Although the 90-day freeze on all tariffs offers a temporary reprieve, the ongoing U.S.-China trade war could still make African exports less competitive in the U.S. market.

For smaller economies such as Lesotho, where 45% of exports go to the U.S., this poses a major risk to jobs and foreign exchange earnings.

Rising costs and imported inflation

While the full economic impact of the 2025 trade war is still unfolding, analysts caution that prolonged tariff disputes between the U.S. and China could drive up global prices. Disruptions in supply chains and increased import costs are likely to put upward pressure on inflation.

The risk of imported inflation is significant for Africa, where many countries rely heavily on imports from China and the U.S., such as machinery, pharmaceuticals, and consumer goods.

Higher import prices, particularly for essentials like food and fuel, could increase the cost of living, especially in countries like Nigeria, Kenya, and Egypt, where these goods constitute a large share of household consumption.

Countries dependent on imports of raw materials and capital goods could also see rising production costs, which may add to inflationary pressures.

As these price increases gradually filter through economies, African central banks will need to balance the challenge of controlling inflation with maintaining economic growth.

Commodity price volatility and fiscal risks

The trade war has sent fresh shockwaves through global commodity markets.

Slowing industrial demand in China, disrupted supply chains, and weakened global confidence have led to declines in prices for key African exports such as oil and copper, while introducing volatility in agricultural commodities like cocoa.

On April 2, following Washington’s announcement of sweeping trade tariffs, Brent crude oil prices fell below $65 per barrel—edging close to Nigeria’s estimated breakeven price of around $60 for its $37 billion budget.

With oil revenues making up around 60% of Nigeria’s income, this price drop places its fiscal position in jeopardy.

A prolonged downturn could lead to spending cuts in health, education, and infrastructure—undermining the country’s development agenda and stalling poverty-reduction efforts.

Angola faces a similar squeeze as the country remains highly dependent on Chinese demand for its crude oil.

A cooling Chinese economy, worsened by retaliatory U.S. tariffs, could curtail Angola’s export earnings, deepen its budget shortfall, and reignite currency pressures.

Already, the kwanza has lost nearly 8% of its value against the dollar since the start of the year.

Copper prices have also taken a hit.

Last week, Citi Research lowered its copper forecast to $8,000 per metric ton, citing the latest tariff announcements from Washington as a key driver of declining demand.

Chile’s state copper agency, Cochilco, also warned that base metal prices have likely peaked amid rising trade tensions. For copper-dependent economies like Zambia, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and Chile, the implications are stark.

In Zambia and the DRC, copper exports account for over 70% and 90% of total export earnings respectively, making these economies acutely vulnerable to price shocks.

Government revenues in both countries are tightly linked to mining royalties and corporate taxes from copper producers.

As prices tumble, fiscal buffers shrink, forcing authorities to make painful budget adjustments or turn to pricey external financing,

Even Chile, the world’s largest copper exporter, is not immune.

Copper contributes about 50% of Chile’s total export value and is a critical source of government revenue through the state-owned miner Codelco.

While the country has historically maintained more prudent fiscal policies, persistent price weakness could undercut its budget forecasts and add pressure to public finances.

For all these countries, the escalating trade war poses not just an external threat but a serious internal risk to economic stability and public sector balance sheets.

Debt vulnerabilities deepen

Rising inflation, dwindling revenues, and increasing borrowing needs are deepening debt vulnerabilities across Africa.

According to the African Development Bank, the continent’s external debt stock surged to $1.15 trillion in 2023, with 25 African countries either already in debt distress or at high risk of falling into it. In 2024 alone, Africa is expected to have spent approximately $74 billion on debt servicing.

With the escalating U.S.-China trade tensions threatening the export revenues of several African countries, these challenges could intensify, making debt management and fiscal stability even harder to maintain.

The situation is particularly dire for countries like Zambia, Ghana, and Ethiopia, where China is a key trading partner.

All three have defaulted on their external debts in recent years, and a prolonged trade war could further erode their foreign exchange earnings, heighten exposure to external shocks, and complicate efforts to meet debt obligations

While a weaker U.S. dollar has eased the cost of servicing dollar-denominated debt, it may also signal trouble. Geopolitical tensions—such as the ongoing U.S.-China trade war—often spook global investors, prompting them to pull capital from emerging markets.

This flight to safety can drain investment from sub-Saharan Africa, making it harder for governments to raise funds.

Countries that once accessed international markets with ease may now face higher borrowing costs—or be locked out entirely.

For major bond issuers like Kenya and South Africa, that translates to pricier loans, rising debt service, and tighter fiscal space. In this way, the trade war’s ripple effects threaten to weaken public finances and limit policy responses across the region.

How Africa can navigate the turmoil

While some African countries could face targeted U.S. tariffs, analysts suggest the direct impact of Washington’s measures on the continent will likely remain limited.

The bigger concern, they argue, lies in the knock-on effects of the rapidly escalating trade war between the two mega-economies.

“The greater risk for Africa is the potential indirect effects of escalating the US-China trade tensions,” said Afreximbank group chief economist Dr Yemi Kale.

In light of this, diversifying trade partners and reducing reliance on external markets are no longer optional but critical for resilience.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) could offer a structural solution.

By fostering regional trade, AfCFTA reduces external exposure and enhances resilience. Countries like Rwanda, Côte d’Ivoire, and Egypt stand to benefit from growing intra-African demand, especially if supply chains are redirected inward and supported by regional infrastructure projects.

There is also growing momentum around African industrialisation.

Countries such as Ethiopia and Morocco—already pushing light manufacturing, agro-processing, and pharmaceuticals—offer blueprints for value addition and export diversification.

Nigeria’s Special Economic Zones, Kenya’s Konza Tech City, and Ghana’s 1D1F (One District, One Factory) initiative represent a shift toward more self-sustaining growth models.

Africa should also deepen engagement with alternative global partners such as India, Brazil, Southeast Asia, and the Gulf states.

These regions offer large consumer markets, investment capital, and less politicised trade relationships. Strategic alignment with such partners could help offset future risks from Western trade policies.