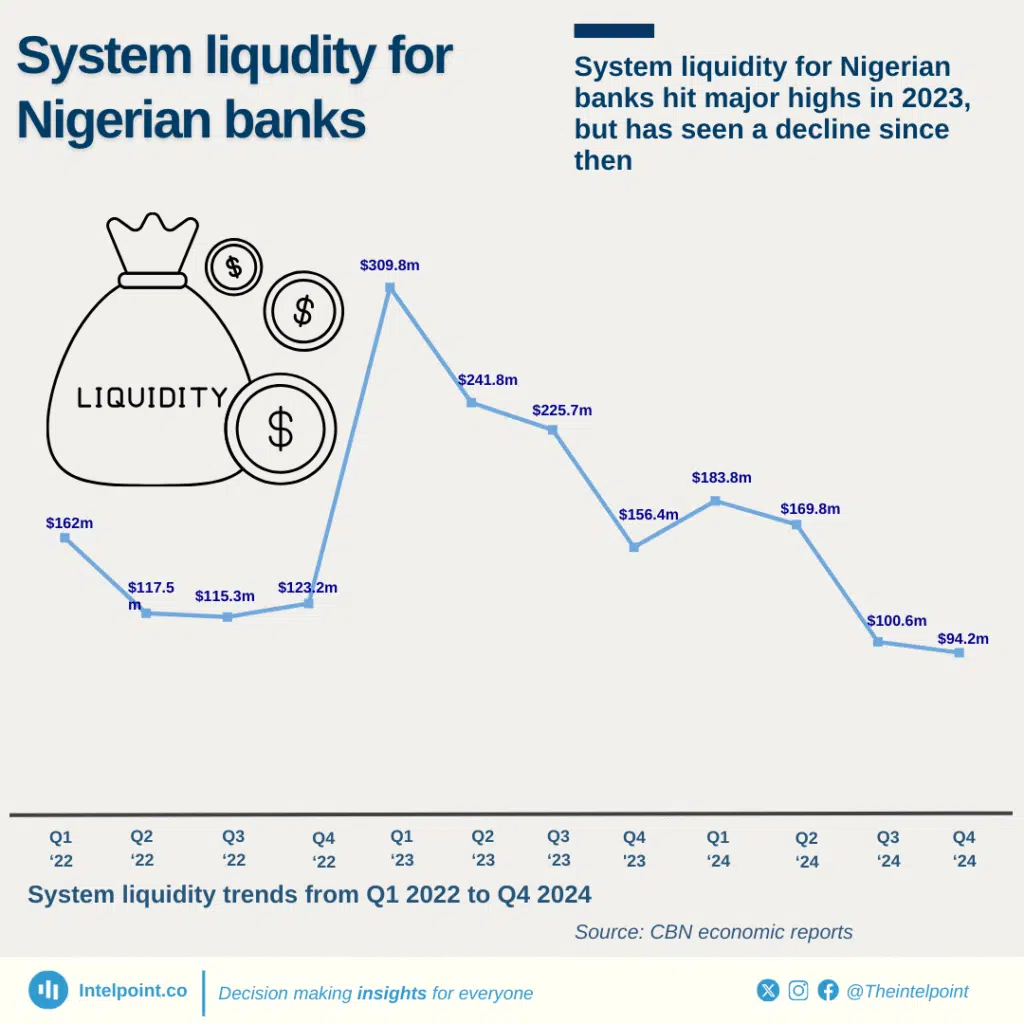

In the three months leading to December 2024, liquidity in Nigeria’s banking system slipped below the $100 million mark for the first time in years — raising concerns about possible stress in the sector.

According to the Central Bank of Nigeria’s (CBN) Q4 Economic Report, banking system liquidity fell to $94.2 million, down 23% from $123 million in the same period of 2022.

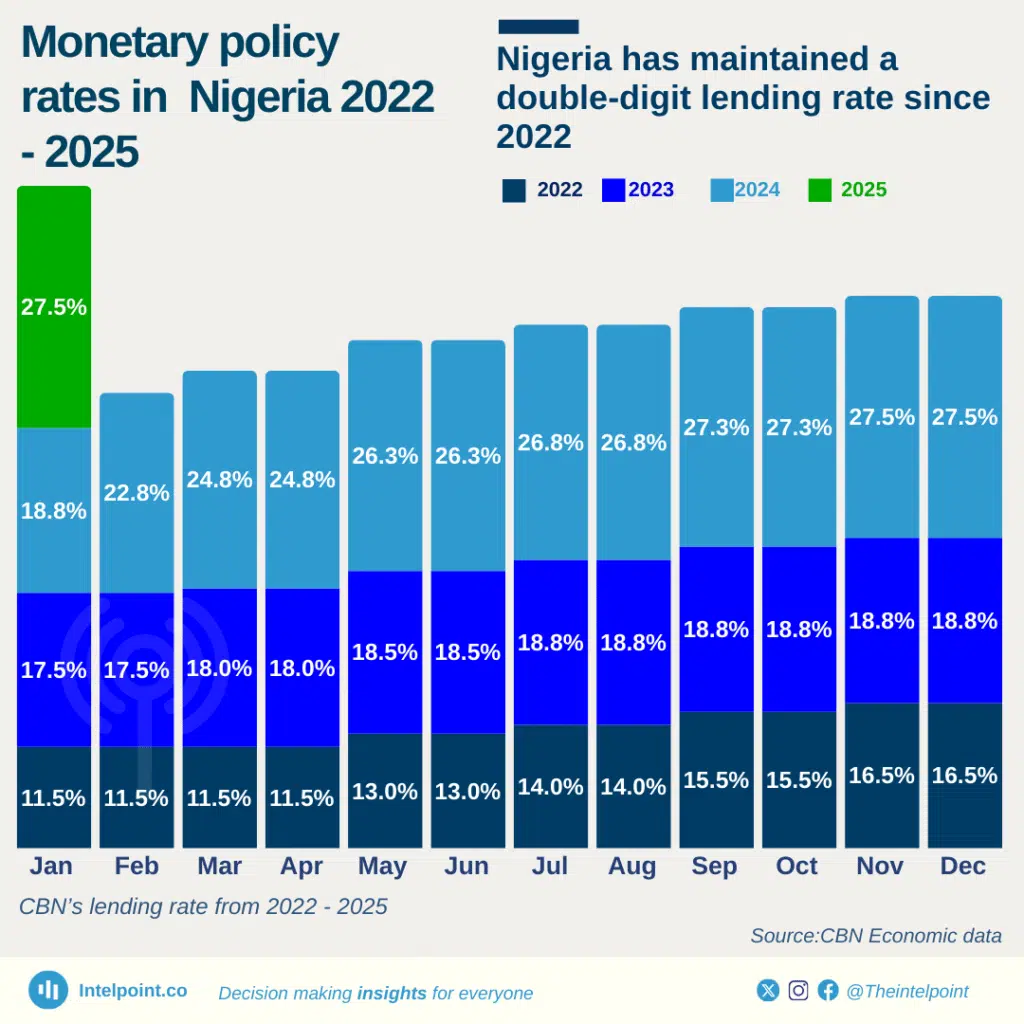

The nearly $30 million drain reflects the apex bank’s hawkish stance, with the Monetary Policy Rate raised by 875 basis points between September 2023 and September 2024, before reaching a 27.5% peak in November.

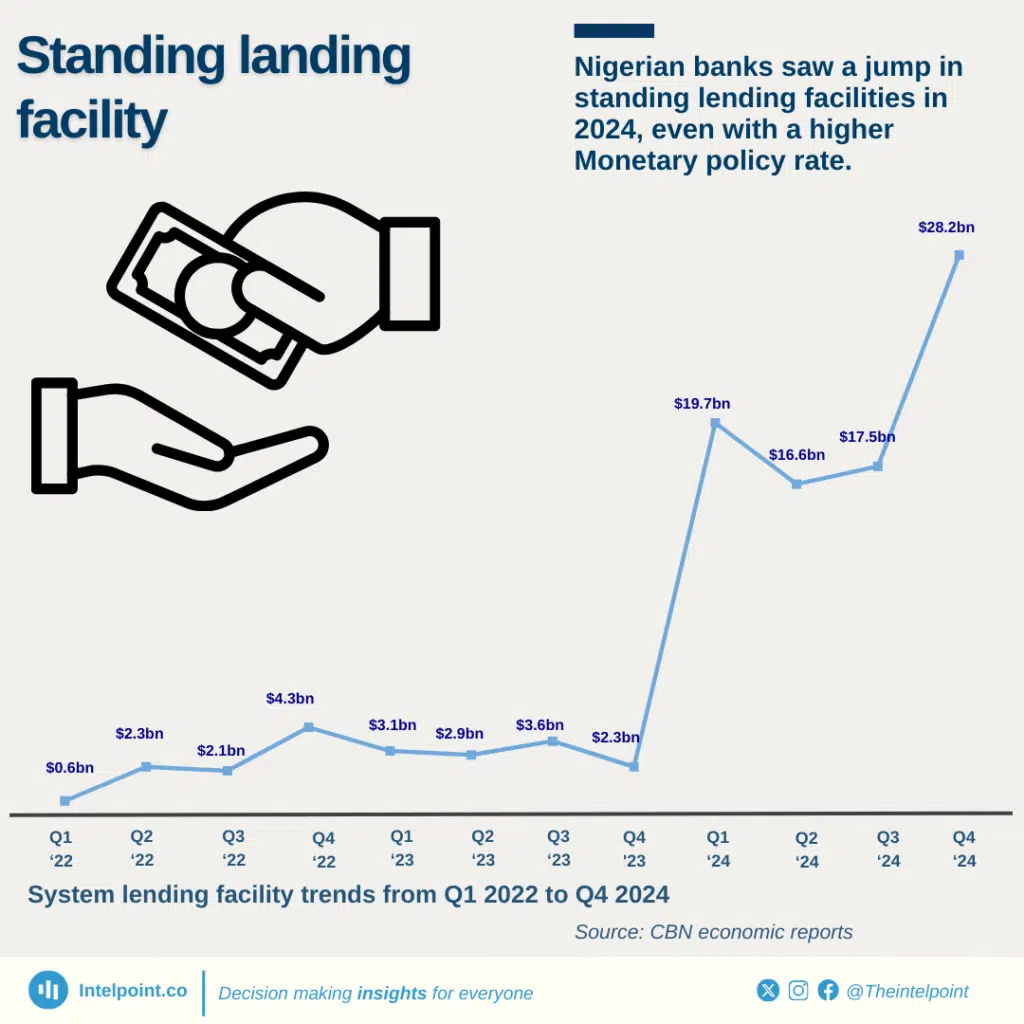

This monetary tightening was matched by a jump in short-term borrowing by banks at the CBN’s Standing Lending Facility (SLF), which rose to $29.1 billion in Q4 2024 from $18.1 billion the previous quarter.

In contrast, placements at the Standing Deposit Facility (SDF) dropped to $7.8 billion from $9.7 billion, indicating that more banks were borrowing rather than parking excess funds.

Despite these signs of strain, Nigerian banks have remained broadly resilient.

Their financial disclosures, capital-raising efforts, and equity market performance all point to continued strength in the face of tightened liquidity.

What’s behind the liquidity drop?

The drop in system liquidity can be traced to a suite of measures by the CBN aimed at curbing inflation and stabilising the naira.

Chief among them is the 50% Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR)—the highest globally—which forces banks to hold half of customer deposits with the central bank, limiting the cash available for lending and investment.

Additionally, the during the fourth quarter of 2024, the CBN has ramped up sales of Open Market Operations (OMO) bills and Nigerian Treasury Bills (NTBs), which mop up naira from the financial system as buyers pay upfront.

Settlement of foreign exchange swap agreements (FX-OMO swaps) has had a similar effect, requiring banks to return naira upon maturity.

These strategies have helped reduce money supply, temper demand for foreign exchange, and attract capital to naira assets, thanks to double-digit yields.

“The idea is to reduce the amount of cash in the system, and that of course will reduce pressure on prices and purchasing,” said financial analyst Kalu Aja in an interview with FinanceIn Africa.

But they’ve also led to a slowdown in credit expansion.

Between January 2024 and January 2025, credit to the private sector dropped from $47.7 billion to $46.7 billion as borrowing became more expensive.

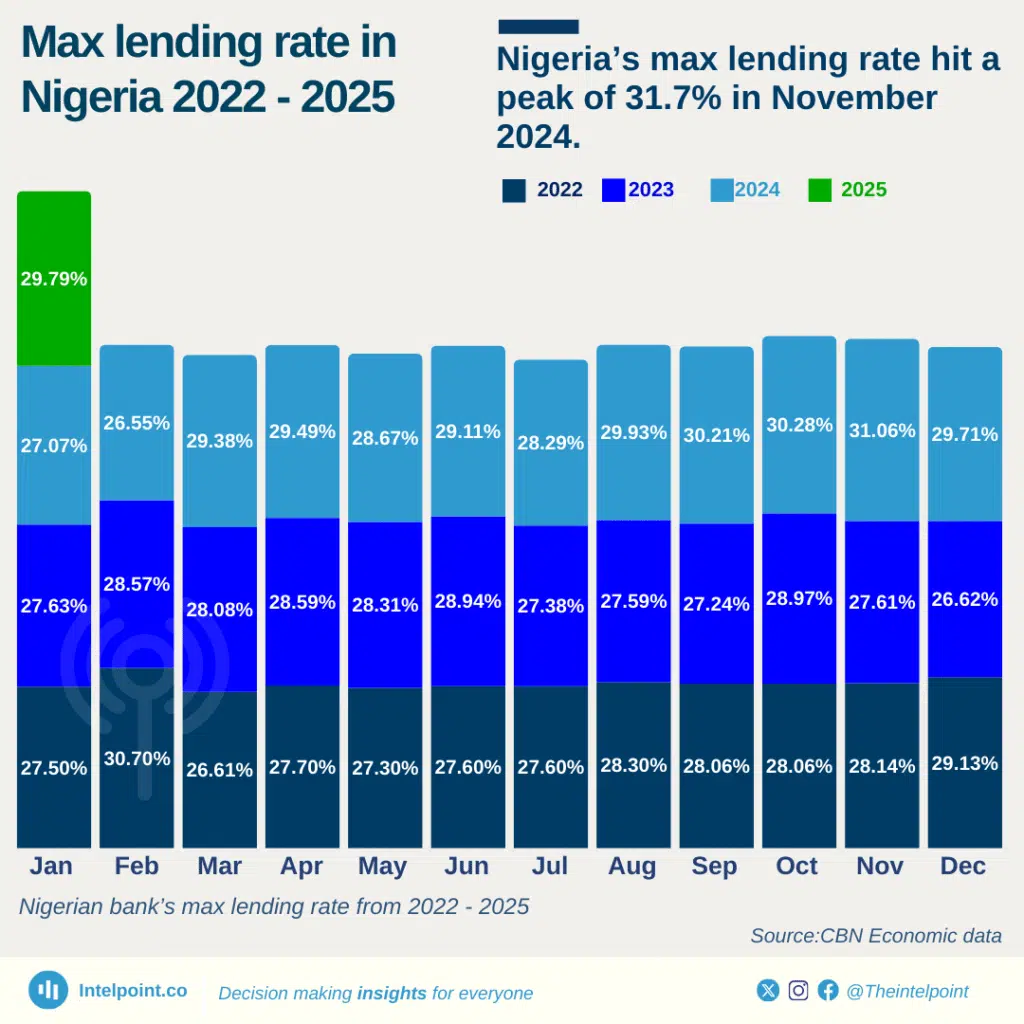

During the same period the maximum lending rate that banks placed on loans to customers surged to 31.06%—the highest since 2019.

However, Aja believes credit growth is being constrained by more than just high reserve requirements.

“In principle, if you reduce the amount of deposits that can be converted to risk assets, you’d expect a decline in the amount of loans banks can write,” he explained.

“But I think the bigger problem is the quality of borrowers in the market. The economy is tough, and entrepreneurs are struggling. So, banks are more reluctant to lend — not because they can’t, but because they’re unsure they’ll be repaid.”

Banks stay profitable despite tight liquidity

While the drain on liquidity is real, not everyone agrees that it has triggered a crisis.

“I wouldn’t categorise what is happening now as a liquidity squeeze,” said Aja. “Look at the last CBN auction: they offered N550 billion ($34.3 million) in securities, and subscription hit N1.08 trillion ($674 million). That tells you banks are still flush with cash and eager to lock in yields.”

He added that the rise in cash in circulation also challenges the liquidity-squeeze narrative. “If you look at other evidence, the amount of cash in circulation is up. There’s a lot of cash out there that is not in the banks.”

Indeed, Nigeria’s currency in circulation reached $3.1 billion in March 2025, with $2.8 billion—over 91%—held outside the banking system. That’s up from $2.3 billion in March 2024.

Furthermore, despite the drop in liquidity, Nigeria banks are turning in record profits.

Nigeria’s top five lenders—Zenith Bank, Access Holdings, UBA, GTCO and First Bank HoldCo—reported a combined profit before tax (PBT) of $3.2 billion in 2024, up 59.4% from $1.9 billion in 2023 according to their latest full year financial statements.

Their gross earnings rose by 80% from $5.9 billion to $10.8 billion over the same period as Zenith Bank led a staggering 67% increase in pre-tax profit.

Even Tier 2 banks – that are highly vulnerable to systemic shocks like a significant drop in liquidity – are riding the profitability wave.

Fidelity Bank’s PBT jumped 180% to $173.5 million, Wema Bank more than doubled its earnings to $64 million, and FCMB Group posted $73.2 million in profit, a 12.3% rise from 2023.

These results have in turn fed into a strong investor appetite. In January 2025, the NGX Banking Index was the best-performing sector index, up 9.76% year-to-date, far outpacing the All-Share Index’s 1.53% growth.

“Bank stocks have been driving the market for a while now,” said Desmond Abbey, investment banker at Hillcrest Capital.

“GTBank and Access bank shares reached unprecedented levels recently, rising to about N70 and N40 respectively.”

According to him, the banks have benefited from a high-yield environment, forex gains, and strong earnings, making investors optimistic about the sector.

Capital buffers get a boost from recapitalisation

Banks are also actively strengthening their balance sheets ahead of the March 2026 deadline for CBN’s new minimum capital requirements.

As of Q1 2025, at least three banks have already met their new capital thresholds, while seven others floated equity offers in 2024, many of which were oversubscribed.

The Securities and Exchange Commission confirmed that roughly $1 billion was raised in new capital within a third of the 24-month recapitalisation timeline.

The new requirements range from $312 million for international banks to $31 million for regional banks. Unlike the previous framework based on shareholders’ funds, the new definition considers only share capital and premium.

To navigate around high CRR debits, some banks are turning to alternative fundraising channels. “Because of the CRR, they don’t have enough cash to run operations,” Eliot explained.

“So what some of them are doing is issuing commercial papers (CPs), which are not currently subject to CRR. It’s expensive — interest can be as high as 28% — but they prefer it to losing 50% of deposits to the CBN.”

Should the CBN stay the course?

Despite the Central Bank’s aggressive monetary tightening, inflation in Nigeria remains stubbornly high, casting doubt on the effectiveness of its hawkish stance.

Although a rebasing of the consumer price basket brought headline inflation down by 10 percentage points in January 2025, the relief proved temporary.

Inflation climbed again to 24.2% in March before edging slightly lower to 23.7% in April. With food prices still surging and structural bottlenecks unresolved, analysts expect upward pressure on prices to persist in the months ahead.

Critics say the current inflation trajectory is less about excessive demand and more about entrenched cost-push factors—particularly insecurity, high transport costs, and weak agricultural output.

“Textbook says you raise rates to fight inflation,” said Aja. “But high rates don’t grow tomatoes. If you raise interest rates, you don’t magically produce more rice—you just reduce people’s ability to buy it.”

That, Aja argues, underscores the limits of monetary policy in today’s context. “There comes a point where high interest rates begin to choke SMEs and the productive economy.

In the past, the CBN recognised this by keeping rates elevated while still channelling subsidised credit to key sectors like agriculture and manufacturing.”

The current administration has largely abandoned that playbook, opting instead for a market-driven approach and tighter fiscal discipline.

But with credit conditions tightening and GDP growth slowing, there are growing calls for a course correction.

For now, Nigerian banks are holding up under the weight of tighter liquidity. But whether they can continue to thrive without broader economic support remains an open question.