As of March 31, 2025, Nigeria’s public debt totaled $97.32 billion (₦149.3 trillion), according to the Debt Management Office. In 2024, the country reportedly spent a total of $8.55 billion (₦13.12 trillion) on debt servicing, representing a 68% increase from the $5.09 billion (₦7.8 trillion) recorded in the previous year. Equally, debt service payments increased by 49.2% year-on-year (YoY) to $2.01 billion ( $3.08 billion) in the first four months of 2025, up from $1.34 billion (₦2.06 trillion) in the same period in 2024.

When assessing the Nigerian National debt profile growth trend, it’s clear the country is dealing with rising debt-servicing obligations, limited revenue, and growing pressure on public finances. For instance, between 2005 and 2025, Nigeria’s government debt growth raises serious concerns about its fiscal health and future economic stability.

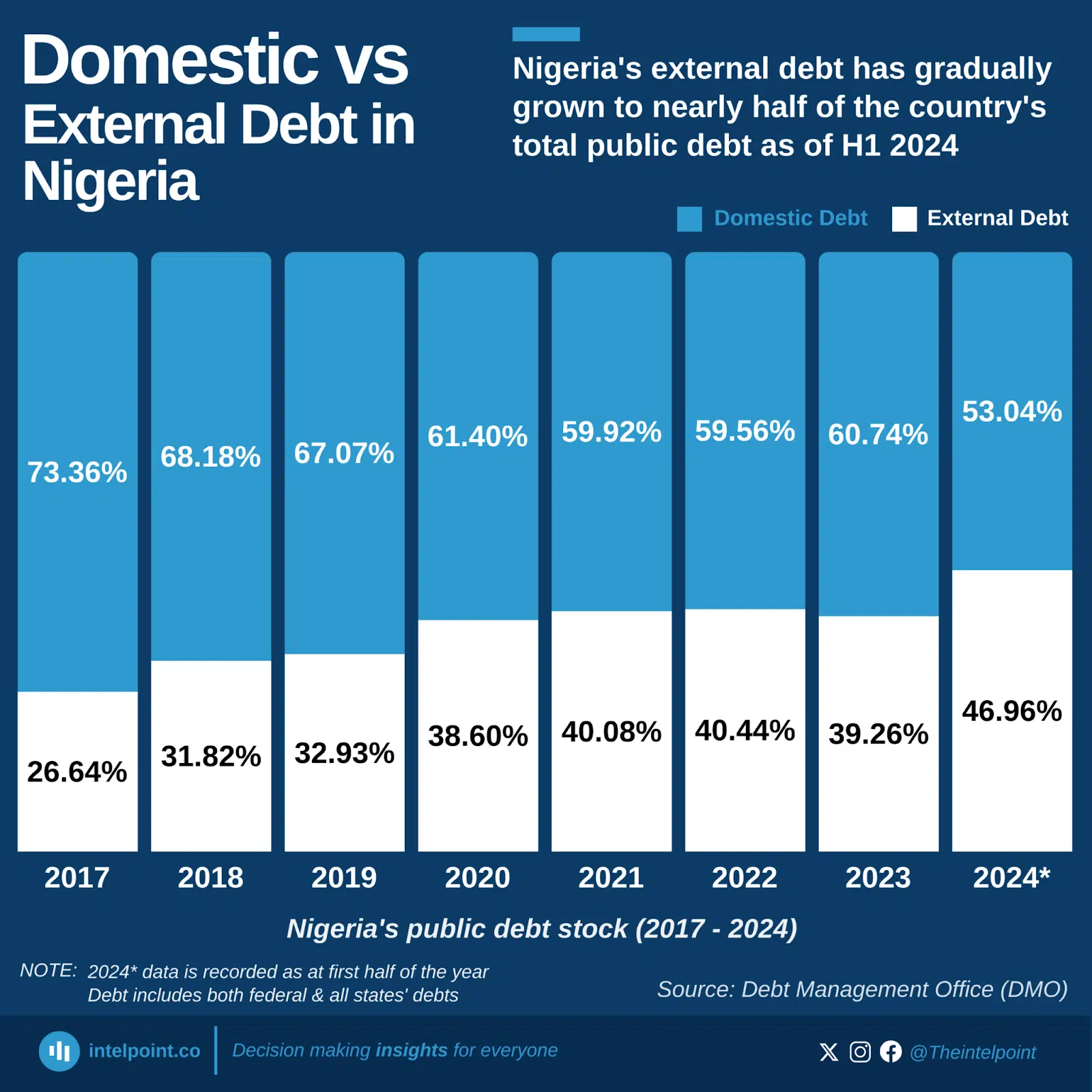

Over the years, aggressive borrowing has contributed to the country’s debt crisis amid increasing reliance on both domestic and external borrowing to finance its budget deficits. As of mid-2024, domestic borrowing accounted for about 53% of the total debt, while external debts stood at around $41.07 billion (₦63 trillion).

As the above reveals only a part of the Nigerian debt trend, this article explores the historical context of Nigeria’s government debt growth. It will examine debt composition, sustainability metrics, fiscal drivers, and implications for economic stability, and also walk you through how the federal government’s debt management strategies have grown in response to both internal and global challenges.

So, whether you’re an economic analyst, investor, policymaker, student, or part of a development finance institution, you are in the right place. Let’s make sense of the Nigerian debt trend together.

Enjoy the read!

Key Takeaways

- Nigeria’s government debt growth raises serious concerns about its fiscal health and future economic stability.

- As of mid-2024, domestic borrowing accounted for approximately 53% of the total debt, while external debt stood at around ₦63 trillion.

- As of March 31, 2025, Nigeria’s public debt totaled ₦149 trillion, equivalent to approximately ₦652,000 per capita.

- Several factors contribute to this reliance on debt, including the COVID-19 Pandemic response, currency devaluation effects, fiscal deficit financing, oil revenue volatility, subsidy payments, and infrastructure financing.

- The key indicators in the Nigerian debt sustainability analysis are the debt-to-GDP ratio, the debt service-to-revenue ratio analysis, the interest payment burden, and the external debt-to-exports ratio assessment

Overview of Nigeria’s debt landscape

As of March 31, 2025, Nigeria’s total public debt stock stood at ₦149.39 trillion (approximately $97.24 billion). This comprises ₦70.63 trillion ($45.98 billion) in external debt, representing 47.28% of the total, and ₦78.76 trillion ($51.26 billion) in domestic debt, which accounts for 52.72%.

Of the domestic debt, the Federal Government was responsible for ₦74.89 trillion ($48.75 billion), while the debt of the 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory amounted to ₦3.87 trillion ($2.52 billion). This composition reflects Nigeria’s ongoing reliance on both domestic and external borrowing to finance its fiscal operations.

From Paris Club debt relief to subsidy removal financing, Nigeria’s debt predicament has intensified to concerning heights in recent times, with forecasts suggesting that the nation’s overall debt could reach ₦187.79 trillion by the end of 2025.

Nigeria’s debt history began with a British government loan of £5.7 million ($7.83 million) in 1923-24, repayable over 20 years at an interest rate of 2.5%. By 1936, a £4.89 million ($6.72 million) loan increased the total to £9.89 million ($13.59 million). External debt remained low until the mid-1970s, reaching $1.5 billion in 1970 (mostly short-term) and $2.5 billion in 1975 ($1.35 billion short-term).

Between 1977 and 1980, uncontrolled borrowing led to a tripling of short-term debt, rising from $3.55 billion to $8.9 billion, with a peak of $7.5 billion reached by 1979.

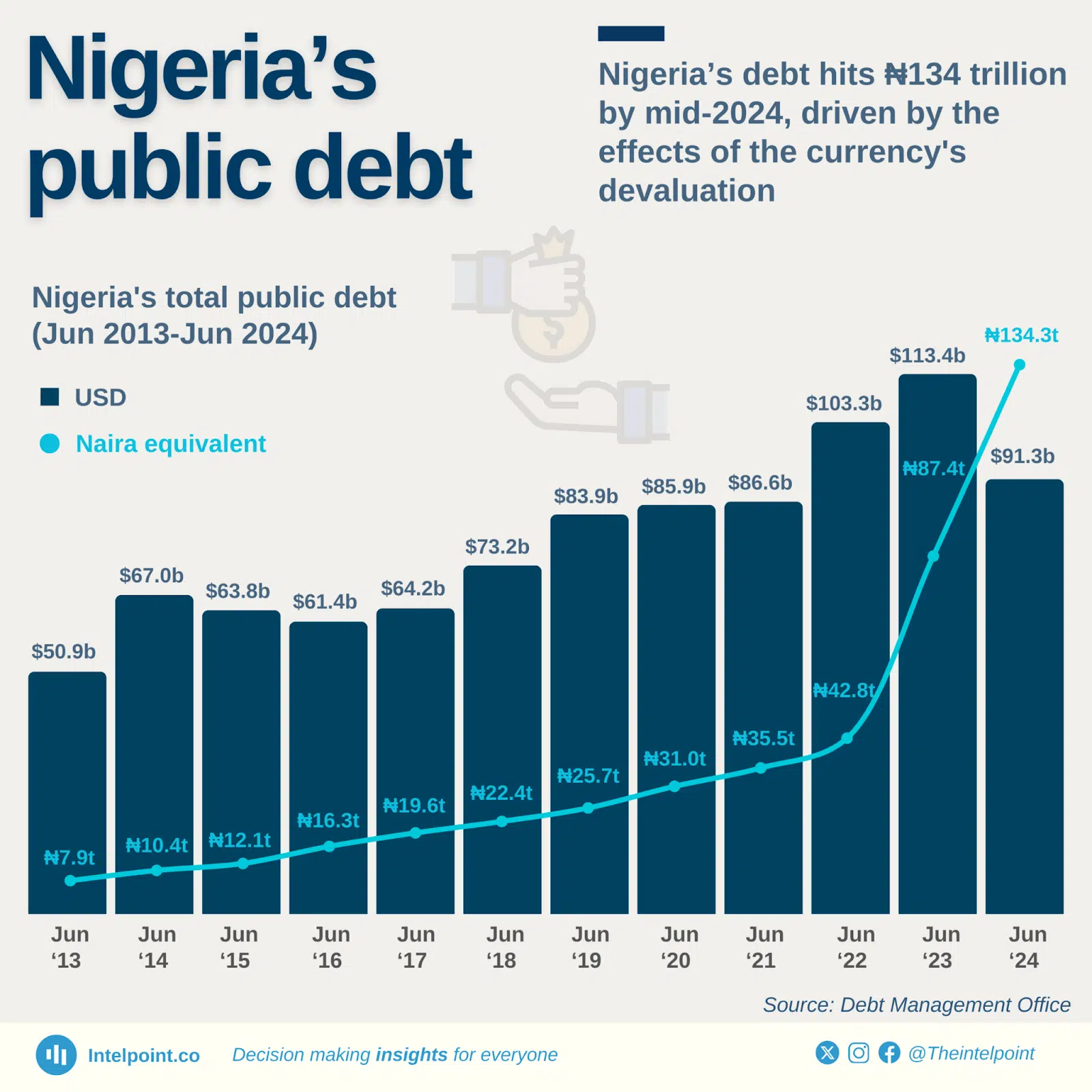

Fast forward to recent times, and the country’s debt continues to grow significantly. According to the BudgIT Foundation, the federal government’s borrowings increased by 658% between 1999 and 2021, from ₦3.55 trillion to ₦26.91 trillion. Following the 2023 general elections, Nigeria’s debt also deteriorated significantly, increasing from ₦49.85 trillion to over ₦134.30 trillion within a short period.

Statista confirms that Nigeria’s debt-to-GDP ratio stood at approximately 52.90% in 2024. Between 1990 and 2024, the rate fell by approximately 18.78 percentage points, although not in a steady pattern. Also, projections suggest a further 7.51% points decline by 2030.

Several factors have contributed to Nigeria’s debt crisis over the years. This includes the country’s reliance on domestic and external borrowing to finance budget deficits, with domestic debt constituting 53% of the total by mid-2024. For a deeper analysis of Nigeria’s fiscal challenges and policy responses, see our comprehensive Nigerian Economic Outlook 2025. Additionally, the Naira’s devaluation, from ₦460 to ₦1500 per dollar between June 2023 and June 2024, inflated the cost of servicing external debts, which stood at ₦63 trillion.

According to BudgIT, poor fiscal discipline, as evidenced by violations of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2007, has led to borrowing for non-productive purposes. Over 80% of government revenue is now allocated to debt servicing, severely limiting funds for essential services such as health and education.

Beyond domestic borrowing, institutions such as the World Bank, the International Development Association (IDA), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the African Development Bank (AfDB) have made significant contributions to Nigeria’s external debt.

Amidst this, there have been suggestions on how to tackle Nigeria’s debt crisis effectively. This includes implementing zero-based budgeting, improving transparency regarding government expenditures and borrowing, promoting economic diversification, and restructuring current debts to lengthen repayment timelines or lower interest rates whenever feasible, to offer immediate relief.

Historical debt profile timeline (2005–2025)

| Year | Total Debt (₦ Trillion) | Total Debt ($ Billion) | Debt-to-GDP Ratio (%) | Domestic Debt (%) | External Debt (%) | Key Debt Event |

| 2005 | 1.9 | 17.5 | 11.2 | 75.8 | 24.2 | Paris Club debt relief |

| 2008 | 3.2 | 26.1 | 13.4 | 69.3 | 30.7 | Global financial crisis impact |

| 2015 | 12.1 | 63.8 | 13.4 | 83.5 | 16.5 | Oil price collapse |

| 2020 | 32.9 | 86.6 | 21.6 | 62.4 | 37.6 | COVID-19 fiscal response |

| 2023 | 87.4 | 103.1 | 31.9 | 52.3 | 47.7 | Subsidy removal financing |

| 2025 | 149.3 | 97.2 | 53.58 | 52.72 | 47.28 | Address the economic challenge |

Understanding national debt: What are domestic and external debts?

Before proceeding to other aspects of the article, it’s crucial to understand the basics, such as what national debt means and its types. You might have heard terms like “domestic debt” and “external debt” thrown around in economic discussions or government briefings, but what do they mean?

National debt is the total amount of money a country owes to its creditors, both within the country and abroad. It’s the accumulation of a nation’s past budget deficits. The two major categories of national debt are domestic and external debt.

What are domestic and external debts?

| Domestic debt | External debt |

| Domestic debt is a debt borrowed by the government within the country | External debt refers to debt borrowed by a government from outside its country. |

| Examples include bonds, treasury bills, and other debt instruments issued by the government and purchased by domestic entities. | Examples include loans from multilateral institutions, bilateral agreements with other countries, and bonds issued on international markets. |

| The sources include the Central Bank of Nigeria, commercial banks, pension funds, and other financial institutions. | The sources include the World Bank, the International Development Association (IDA), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the African Development Bank (AfDB), and other bilateral creditors. |

Amid this, there are downsides. I discovered that external debt often comes with strict conditions and higher interest rates, whereas domestic debt is more flexible. Meanwhile, too much reliance on either of them can be risky. Too much external debt can affect a country’s foreign currency, while excessive domestic debt can limit the money available for private businesses.

Domestic debt analysis

- Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN) Bonds composition

FGN Bonds are typically long-term investments ranging from 3 to 50 years issued by the Debt Management Office (DMO) on behalf of the Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN). The FGN must pay the bondholder the principal and agreed interest as and when due.

- Nigeria Treasury Bills (NTB) and savings bonds

Nigerian Treasury bills are short-term debt securities issued by the government to offset budget deficits and fund projects. They are issued by the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) on behalf of the federal government. Meanwhile, the FGN Savings Bonds are debt securities issued by the Nigerian government through the Debt Management Office (DMO) to raise funds for development projects.

When you buy an FGN Savings Bond, you are lending money to the Nigerian government. In return, the government pays you interest on your investment, typically every quarter, over a specified period.

- Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) Ways and Means advances

These are short-term loans from the CBN to the Federal Government to cover temporary budget shortfalls, authorized under the CBN Act.

- Sukuk bonds

These are Sharia-compliant financial instruments that are similar to conventional bonds but adhere to Islamic finance principles. They represent ownership in an asset or project rather than a loan, offering a yield based on the performance of the underlying asset.

In Nigeria, Sukuk bonds have been used by both the federal and sub-national governments, as well as private entities, to fund various projects.

- Green bonds

These are debt instruments specifically used to finance environmentally friendly projects. They are becoming increasingly popular as governments and organizations seek to address climate change and promote sustainable development. A June report stated that the Debt Management Office (DMO) had issued a 50 billion green bond to support the Federal Government’s initiatives in environmental sustainability.

External debt analysis

- Multilateral debt (World Bank, AfDB, IMF)

Multilateral debt refers to the debt a country owes to international financial institutions (IFIs) such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). These institutions provide loans and grants to developing countries to support economic development and address balance-of-payments issues.

- Bilateral debt (China, France, India, Germany)

Bilateral debt refers to loans or credit extended by one country directly to another. This contrasts with multilateral debt, which involves loans from international organizations like the World Bank or the IMF. Major bilateral lenders to Nigeria include countries like China, France, India, and Germany.

- Commercial debt (Eurobonds, syndicated loans)

This refers to borrowings obtained from private investors and financial markets rather than from governments or development agencies. Examples include eurobonds and syndicated loans. For instance, as of June 2024, Nigeria’s Eurobond debt was approximately $15.12 billion, accounting for about 35% of its total external debt of $42.9 billion. Equally, the Bank of Industry secured a $1 billion syndicated term loan in the International market in December 2020.

Major drivers of Nigeria’s government debt growth

Over the last years, several factors have contributed to Nigeria’s government increasing reliance on debt, both domestically and externally. Below is a breakdown of the key drivers:

Infrastructure financing (2007-2025)

Between 2007 and 2025, Nigeria’s government increasingly borrowed to fund major infrastructure projects in sectors like power, transportation, and social infrastructure investments. Without moving too far backward, in 2017, the federal government raised a ₦100 billion seven-year debut sukuk bond for the financing of 25 road projects across the country’s six geo-political zones.

Also in 2024, the federal government raised ₦1.1 trillion to finance 124 federal road projects covering over 5,820 kilometers across the country’s six geopolitical zones. The latest announcement was made in May 2025, when the Debt Management Office (DMO) issued a ₦300 billion 7-year Ijarah Sukuk bond to fund critical road and bridge infrastructure across Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones.

While the above are only a few instances of borrowing to fund road projects, there are other instances for the power sector and other means of transportation, particularly the railway.

An example in the power sector is the Zungeru Hydroelectric Power Station, a 700 MW project in Nigeria, primarily funded by a loan from the China Exim Bank, covering 75% of the estimated $1.3 billion cost. Also, both the Abuja-Kaduna railway, completed in 2016, and the Lagos-Ibadan railway, commissioned in 2021, were primarily financed through loans from the China Exim Bank. Education and housing schemes are also not exempt.

Oil revenue volatility and subsidy payments

Crude oil price shocks and revenue shortfalls are another major driver of the federal government’s debt profile. In 2022, the Director-General of the Debt Management Office, Ms. Patience Oniha, confirmed that the nation’s public debt stock increased because of the petrol subsidy, as the government had to borrow N1 trillion to subsidize petrol that year.

Fiscal deficit financing

In Nigeria, fiscal deficit financing, which involves borrowing to cover government spending exceeding revenue, has significantly contributed to the country’s rising national debt. This reliance on borrowing, both domestically and externally, has led to increased debt servicing costs and reduced funds for critical sectors. While the country increasingly relies on domestic and external borrowing to finance its budget deficits, as of mid-2024, domestic borrowing accounted for about 53% of the total debt, and external debts stood at approximately ₦63 trillion.

Currency devaluation effects

The naira depreciation impact is another key driver of Nigeria’s government debt growth. In 2024, the Punch report confirmed that the Naira devaluation increased Nigeria’s external debt by approximately N30.03 trillion between 2023 and June 2024, when considered in Naira terms.

Additionally, the Naira experienced a significant devaluation by the end of 2023, falling approximately 53% year-over-year from ₦424 to ₦ 200. This depreciation continued into early 2024, with the naira reaching ₦1,544 by February. This rapid decline in the naira’s value significantly increased the cost of Nigeria’s dollar-denominated debt due to exchange rate fluctuations.

COVID-19 Pandemic response

Government spending and fiscal deficits rose due to the COVID-19 pandemic, necessitating emergency borrowing and stimulus financing. In April 2020, Nigeria secured $3.4 billion through the International Monetary Fund’s Rapid Financing Instrument to mitigate the economic shocks caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nigerian debt sustainability analysis

With Nigeria’s increasing reliance on debt, sustainability becomes paramount. The country has faced fluctuating debt levels, sparking debates about the need to strike a balance between borrowing and sustained economic growth. Debt sustainability refers to a country’s ability to meet its debt obligations without requiring debt relief or accumulating arrears. It ensures that a country can meet its debt obligations without compromising its ability to invest in essential services, promote economic growth, and foster future development.

Debt sustainability is essential, particularly for a country like Nigeria. It prevents debt distress and economic instability, promotes investor confidence and access to finance, facilitates international cooperation, supports economic growth and development, and protects future generations by ensuring past borrowing decisions do not unduly burden them.

To further exemplify the importance of debt sustainability, the World Bank Group and the IMF work with low-income countries to produce regular Debt Sustainability Analyses, which are structured examinations of developing country debt based on the Debt Sustainability Framework.

Key indicators of debt sustainability

- Debt-to-GDP ratio

The debt-to-GDP ratio is a vital indicator, as it illustrates the relationship between a country’s total debt and its gross domestic product (GDP). Nigeria’s debt-to-GDP ratio increased to 52.1% in 2024, up from 41.5% in 2023, bringing it closer to the IMF’s 55.0% threshold for assessing debt sustainability risks.

- Debt service-to-revenue ratio analysis

A debt service-to-revenue ratio indicates the proportion of government revenue allocated to debt repayments. A rising debt-service-to-revenue ratio means that a large percentage of the government’s revenue, which should be used for capital expenditures, is allocated to pay off debt commitments.

In 2022, Nigeria’s debt service-to-revenue ratio was 80.6%, a figure significantly higher than the World Bank’s recommended 22.5% for low-income countries. Fast forward to 2024, debt service costs surged by 69% year-on-year to 6 trillion in the first six months, consuming about half of the federal government’s aggregate expenditure. This highlights the significant burden of debt obligations on the government’s finances.

- Interest payment burden and crowding-out effects

The interest payment burden refers to the cost a government incurs from paying interest on its debt. This burden can lead to a crowding-out effect where increased government spending, often financed by borrowing, raises interest rates, thus reducing private investment and potentially hindering economic growth.

- External debt-to-exports ratio assessment

Nigeria’s external debt-to-exports ratio is a key indicator of its ability to service its foreign debt obligations. According to the World Bank, Nigeria’s external debt in 2023 accounted for 71.78% of its exports of goods, services, and primary income. This ratio highlights the extent to which Nigeria’s export earnings are used to pay back its external debt.

Fiscal space evaluation

Fiscal space evaluation in Nigeria involves assessing the government’s capacity to increase public spending without compromising its financial stability. This analysis examines the availability of resources for specific sectors, including social protection, health, and education.

In Nigeria, debt stabilization requires a positive primary balance, where revenue (excluding interest) exceeds spending. This helps reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio in the long run and fosters stronger fiscal discipline, making sustainable budgeting a crucial component.

Also, contingent liability risks, which are potential future obligations that may arise depending on the occurrence or non-occurrence of a specific future event, are another challenge. According to the World Bank, countries across all continents face the challenge of managing contingent liabilities arising from multiple sources, including state-owned enterprises (SOEs), parastatals, off-budget financing arrangements, and civil servant entitlement schemes.

To address this, effective management of these risks is essential.

Stress-testing scenarios

Stress testing is an integral part of debt sustainability analysis. It helps to evaluate how Nigeria’s debt profile is vulnerable to economic shocks. These scenarios include oil price shock, exchange rate depreciation, growth slowdown, and debt dynamics.

- Oil price shock impact on debt sustainability

Nigeria’s heavy reliance on oil revenue has often led to the adverse effects of oil price shocks. Fluctuations in global oil prices can lead to reduced government revenue, potentially widening fiscal deficits and increasing borrowing, which puts the country at risk of being unable to meet its debt obligations.

- Exchange rate depreciation sensitivity analysis

Another critical factor is exchange rate depreciation. It increases the cost of servicing external debt. For instance, if the naira weakens, the cost of repaying external debt denominated in foreign currencies rises, straining the national budget. Eurobonds fall under this category.

Additionally, a sustained slowdown in economic growth would reduce government revenue and increase the debt-to-GDP ratio, making it harder to maintain a stable debt trajectory. Together, these scenarios test the resilience of Nigeria’s fiscal framework and highlight the importance of prudent debt management and economic diversification.

- Growth slowdown and debt dynamics

In recent years, Nigeria has experienced a slowdown in economic growth, with GDP growth rates fluctuating. Various factors influence this slowdown, including the global economic climate, fluctuating oil prices, and domestic challenges like insecurity and infrastructure deficits.

If growth remains slow, the country tends to have issues with debt sustainability.

Strategies for sustainable debt management in Nigeria

Nigeria requires effective strategies to manage its debt and maintain economic stability. Below are some strategies for sustainable debt management:

Fiscal discipline

The country needs to implement transparent budgeting processes that ensure that government spending aligns with realistic revenue projections. This helps avoid excessive borrowing and contributes to maintaining a stable debt-to-GDP ratio.

Diversify financing sources

Over-reliance on conventional loans makes one more vulnerable. The country should explore alternative mechanisms, such as public-private partnerships (PPPs) and green bonds, which can attract investment while minimizing debt burdens and exposure to interest rate and currency risks.

Develop a comprehensive debt management strategy

Continuous monitoring and evaluation of the national debt portfolio is key to a sound debt management framework. This enables quicker risk assessment and well-informed borrowing choices.

Another strategy is that the country should improve tax collection and expand its tax base. Low tax rates, widespread exemptions, poor compliance, and a narrow indirect tax base contribute to Nigeria’s low tax revenue. Tax compliance and tax morale are still very low.

Regional debt comparison: Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya & South Africa

Debt levels in African countries are rising rapidly, with the debt burden increasing significantly over the past 15 years. Since the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC), the continent’s aggregated debt-to-GDP ratio has surged by 39.3 percentage points between 2008 and 2020, and then declined to 68.6% of GDP in 2023.

The continent has also experienced a significant increase in external debt since 2008, reaching $1.2 trillion and accounting for nearly 60% of the region’s total public debt stock as of 2023.

According to Afreximbank’s State of Play of Debt Burden in Africa 2024 report, ten African countries bore about 67% of Africa’s total external debt stock: Egypt (14.5%), South Africa (14.3%), Nigeria (8.4%), Morocco (5.9%), Mozambique (5.5%), Angola (5.3%), Kenya (3.7%), Tunisia (3.4%), Sudan (3.1%), and Ghana (3.0%), respectively.

Amid this challenge, Africa’s debt-to-GDP ratio is forecasted to decline by 2028, bolstered by improved economic growth and the adoption of longer-term debt instruments.

Before presenting a table for a regional debt comparison, let’s examine the national debt trends of the countries.

According to Statista, the ratio of national debt to gross domestic product (GDP) of Ghana was estimated at approximately 70.51% in 2024. Between 1990 and 2024, the ratio increased by approximately 52.72% points. However, the ratio is expected to decline by approximately 18.55 percentage points between 2024 and 2030, indicating a continuous downward trend throughout the period.

Meanwhile, in 2024, the ratio of national debt to gross domestic product (GDP) of Nigeria was approximately 52.90%. Between 1990 and 2024, the figure dropped by around 18.78% points with the forecast showing the ratio will steadily decline by about 7.51% points from 2024 to 2030.

For Kenya, the ratio of national debt to gross domestic product (GDP) stood at approximately 65.59% in 2024. Between 1998 and 2024, the ratio increased by approximately 27.09 percentage points. However, the ratio is forecast to decline by approximately 1.16 percentage points from 2024 to 2030, fluctuating as it trends downward.

South Africa’s ratio of national debt to gross domestic product (GDP) was about 76.36% in 2024. Between 2000 and 2024, the ratio increased by approximately 38.43 percentage points. It is also projected to rise steadily by around 12.37% points over the period from 2024 to 2030, reflecting a clear upward trend.

| Country | Total Public Debt (Billions) | Debt-to-GDP Ratio | Key factors |

| Nigeria | $97.2 (2025) | 52.90% (2024) | Aggressive borrowing, naira devaluation, weak fiscal discipline, and a large portion of revenue going to debt service. |

| Ghana | $49.5(2025) | 70.51 (2024) | Persistent budget deficits, high debt service costs, |

| Kenya | $82.5(2025) | 65.59% (2024) | Persistent fiscal deficits, rising debt servicing costs, shortfalls in revenue collection, and economic shock. |

| South Africa | $310.9(2024) | 76.36% (2024) | Increased government spending, economic slowdown, and global economic shock. |

Conclusion

Now, you know Nigeria’s government debt growth raises serious concerns about its fiscal health and future economic stability, with the country’s increasing borrowing attitude. Several factors contribute to this reliance on debt, including the COVID-19 Pandemic response currency, devaluation effects, fiscal deficit financing, oil revenue volatility, subsidy payments, and infrastructure financing.

Meanwhile, to ensure debt sustainability, recommendations include adopting zero-based budgeting, enhancing transparency through detailed debt and expenditure reports, and diversifying into non-oil sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing to reduce oil dependency. Strengthening the Fiscal Responsibility Act with stricter enforcement and exploring public-private partnerships and green bonds. Improved tax collection is also crucial in addressing low revenue.

In February, the Federal Government of Nigeria signed the 2025 Appropriation Act into law, approving a budget of ₦54.99 trillion. Of this, ₦14.32 trillion, about 39% of projected revenue, is allocated to debt servicing. The budget sets a revenue target of ₦36.35 trillion. The government aims to boost tax collection and expand non-oil revenue streams to meet this target.

To make this work, policymakers, investors, and citizens must demand transparent fiscal policies, support the growth of the non-oil sector, and hold leaders accountable to secure Nigeria’s economic future.

Disclaimer

This publication, review, or article (“Content”) is based on our independent evaluation and is subjective, reflecting our opinions, which may differ from others’ perspectives or experiences. We do not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the Content and disclaim responsibility for any errors or omissions it may contain.

The information provided is not investment advice and should not be treated as such, as products or services may change after publication. By engaging with our content, you acknowledge its subjective nature and agree not to hold us liable for any losses or damages arising from your reliance on the information provided. Always conduct your research and consult professionals where necessary.