Walk through a Lagos market today and you’ll see a quiet revolution. The tomato seller no longer worries about cash; they accept transfers, cards, and QR codes with the same ease.

That ordinariness hides a decade of deliberate engineering: Nigeria built open rails for money, where any wallet can pay any bank, QR codes talk across apps, and merchants accept payments from anywhere.

It is one of the country’s few unambiguous macroeconomic bright spots. The results speak for themselves. Cashless transactions reached ₦611 trillion ($437 billion) in 2023 and surged past ₦1 quadrillion ($661 billion) in 2024. Real-time transfers are now the default way to pay. Competition has thrived because any licensed provider can reach any account.

Banks and fintechs compete on price, uptime, and user experience, not on closed networks. That is why Nigeria ranks among the world’s leaders in instant payments and why digital acceptance has become routine from petrol stations to roadside kiosks.

The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) deserves credit for embedding interoperability in its Payments System Vision 2025 and requiring open access across issuers, acquirers, and switches. The social payoff has been huge: financial inclusion climbed to 64% in 2023 from 56% just three years earlier, while exclusion fell to 26%.

Tens of millions now send money, save, or get paid without touching cash. Government transfers reach citizens faster, informal businesses formalise, and women, who face higher barriers, gain safer ways to transact and build credit. But one bottleneck risks undoing this progress: exclusivity in card processing.

Cards break the pattern of openness

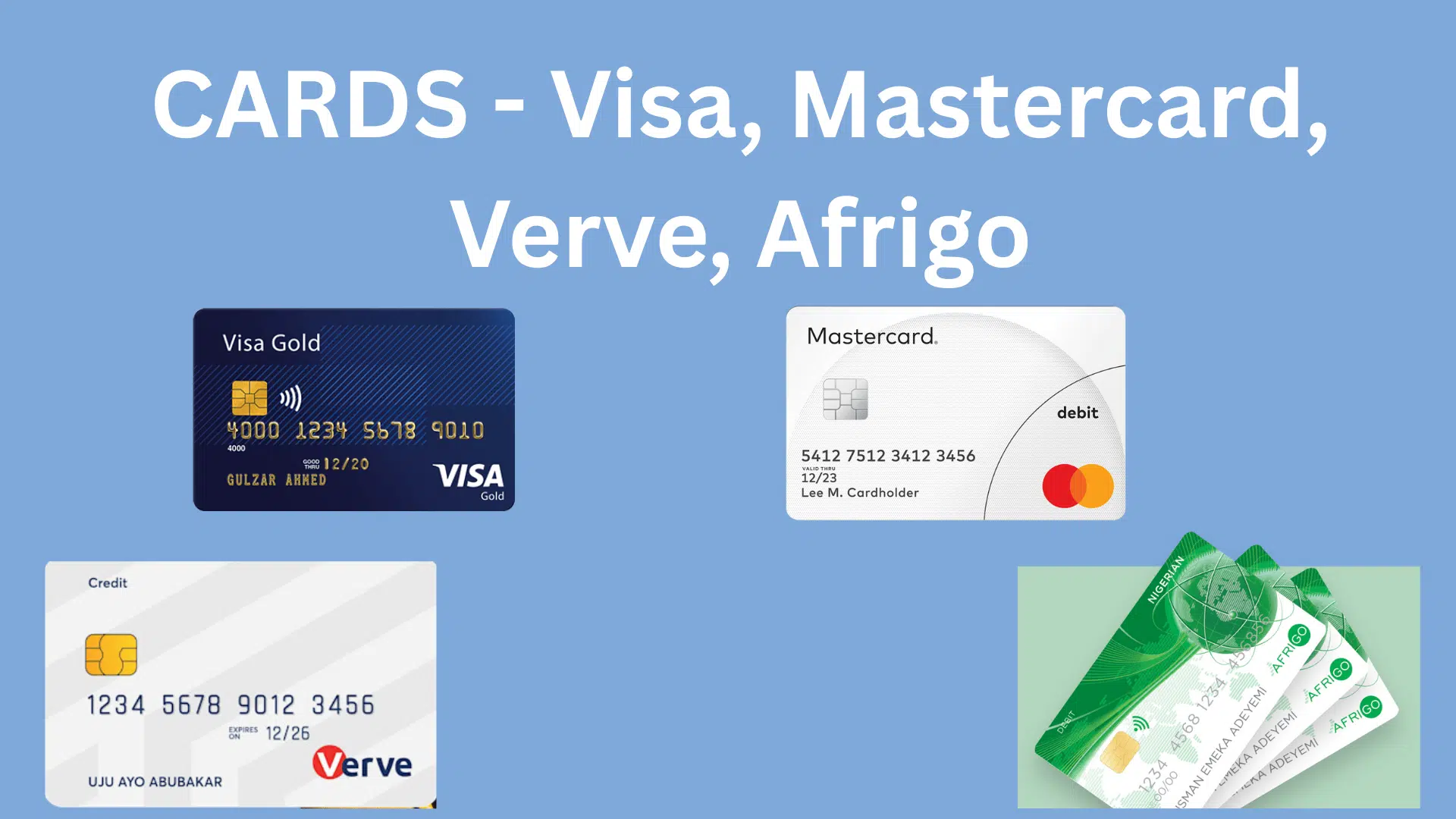

Domestic schemes such as Verve and AfriGo currently restrict processing to their proprietary switches. This means merchants and consumers lose the same benefits they take for granted elsewhere: least-cost routing, redundancy when a processor goes down, and price competition. It is a quiet form of rail capture, one that raises costs, concentrates power, and chills innovation.

This is not how we treat international card networks. Visa and Mastercard transactions can route through multiple processors, giving acquirers flexibility and merchants lower costs. Nor does exclusivity align with Nigeria’s own rules: QR frameworks demand interoperability, and open-banking guidelines widen, not narrow, access. Cards should be no different. The fix is straightforward.

We urge the CBN to mandate scheme-neutral switching, so any licensed processor that meets security standards can handle domestic cards. Secondly, separate scheme governance from switching businesses to prevent self-dealing. Publish quarterly metrics on uptime, routing availability, and pricing to shine light on performance.

These are familiar tools for regulators worldwide. The urgency is clear. In 2024, more than 11 billion transactions moved across NIBSS rails. Each new merchant, wallet, or app adds value for every other user.

Each carve-out does the opposite: it fragments the network and raises the price of trust. Interoperability is not just a technical term; it is the constitutional principle of a modern digital economy.

Nigeria has already shown the world what open payment rails can achieve: explosive growth, deeper competition, and broader inclusion. Keeping card processing as open as transfers is the logical next step.

Do it now, and Nigeria will continue to lead. Delay, and we risk watching the tomato seller in Lagos once again ask, “What card do you carry?” before she can take your money.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or positions of Finance in Africa or its parent company. Guest contributions are published to encourage informed debate and diverse perspectives within Africa’s financial services ecosystem.

Benjamin Odey is a financial inclusion expert based in Lagos, Nigeria. He has written on the subject of digital payments and their role in promoting financial inclusion.

Odey has canvassed at different fora for open and interoperable payment rails that make it easier for people to send money, save, transact and build credit, especially informal businesses.

Odey’s background also includes work as a project manager in Lagos. He has experience in helping companies move from the idea stage to profitability, and has worked on projects related to agriculture, digital marketing, and web development.