Africa’s monetary authorities are exploring a new way to turn one of the continent’s oldest commodities into modern financial infrastructure.

The Central Bank of Egypt and African Export–Import Bank have signed a memorandum of understanding to establish a pan-African Gold Bank programme, a move aimed at formalising gold value chains, strengthening central bank reserves and reducing Africa’s reliance on offshore refining and trading hubs.

While framed as a feasibility study, the initiative points to a deeper shift in how African policymakers are thinking about gold: not just as an export commodity, but as a strategic monetary and balance-sheet asset.

The production–reserves gap

Africa is one of the world’s largest gold-producing regions, accounting for more than a quarter of global output. Yet African central banks collectively hold only a small fraction of the world’s official gold reserves.

Publicly available data show that African central banks together hold just over 700 tonnes of gold, roughly 2% of global central-bank gold holdings, despite the continent’s outsized production footprint. North Africa dominates those reserves, with Algeria, Libya and Egypt among the largest holders.

This imbalance reflects a long-standing pattern: gold is mined in Africa, but refined, vaulted, traded and often priced elsewhere. Much of the continent’s gold flows through hubs in the Middle East and Europe, bypassing African financial systems entirely.

Industry and law-enforcement estimates suggest that tens of billions of dollars’ worth of African gold leaves the continent informally each year, undermining tax collection, foreign-exchange availability and the ability of central banks to build reserve buffers from domestic resources.

The proposed Gold Bank programme is designed to address that leakage by anchoring refining, vaulting and associated financial services on the continent.

From commodity to monetary asset

Under the MoU, the CBE and Afreximbank will commission a feasibility study covering the technical, commercial and regulatory requirements for an integrated gold-banking ecosystem. The concept includes an internationally accredited refinery, secure vaulting facilities and gold-linked financial and trading services, potentially located in a designated free zone in Egypt.

For central banks, the attraction is clear. Gold is a reserve asset that carries no sovereign credit risk, provides diversification against currency volatility and can enhance confidence in domestic monetary frameworks when held transparently and at scale.

Speaking at the signing, Hassan Abdalla, governor of the Central Bank of Egypt, described the initiative as a foundation that could expand into a broader pan-African framework involving governments, central banks and market participants.

He noted that Egypt’s selection as a potential hub reflects confidence in its institutional readiness and geographic position linking Africa, the Middle East and Europe.

The emphasis on geography is not incidental. Control over refining, storage and trading infrastructure determines who captures value, pricing power and financial optionality from gold flows.

Afreximbank’s strategic calculus

For Afreximbank, the initiative fits into a broader push to keep African resources on African balance sheets.

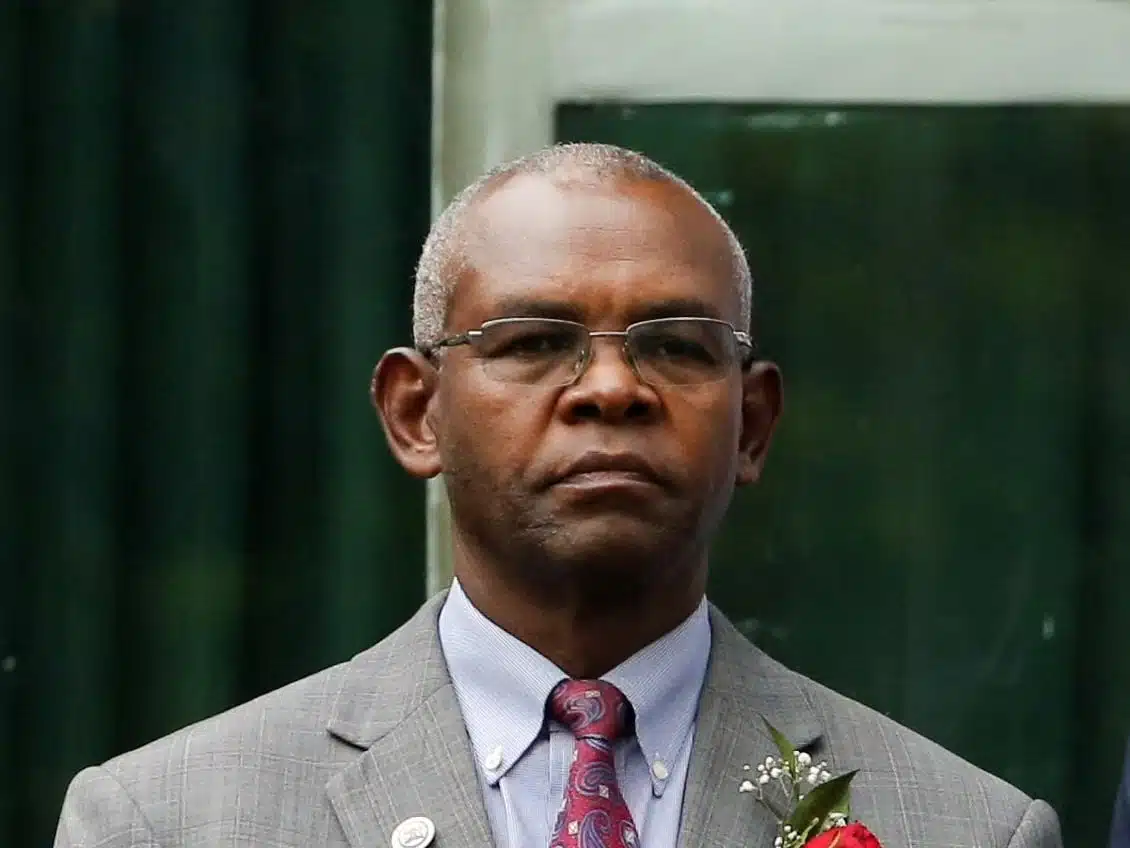

George Elombi, president and chairman of Afreximbank, framed the project as an attempt to fundamentally change how Africa extracts, refines, manages and trades its gold.

“By effectively building up the gold stock, as other major economies have done, we enhance the continent’s resilience, minimise vulnerability to external shocks, improve currency stability and convertibility, and create wealth within the continent,” Elombi said.

That language echoes global trends. Over the past decade, central banks in several emerging and non-Western economies have increased gold allocations as a hedge against dollar dependence, sanctions risk and external financial tightening. Africa, despite its resource base, has largely remained on the sidelines of that shift.

Egypt’s positioning — and continental implications

Egypt’s broader push to become a regional gold hub predates the Gold Bank MoU. In August 2025, the government advanced a draft law to certify domestic gold refineries and create a regulatory framework for gold investment funds, intended to open new channels for institutional and retail participation in the sector.

Officials framed these reforms as part of a strategy to strengthen the country’s position in regional bullion markets and align refining and investment activity with international standards. These steps laid the groundwork for more ambitious initiatives, underscoring that the Gold Bank programme is a continuation of Cairo’s long-term effort to integrate gold into financial and reserve frameworks.

Egypt already holds one of Africa’s largest official gold reserves and has been actively rebuilding its broader external buffers. Hosting a continental gold-banking platform would reinforce its role as a financial and trading hub, while tying its own reserve strategy more closely to African supply chains.

But the implications extend beyond Egypt.

A wave of domestic efforts to capture more value from gold has been gathering momentum across the continent. Ghana, Africa’s leading producer, is preparing to refine gold locally from October 2025 and transition from exporting raw doré to producing bullion with internationally recognised fire assay testing

. Mali is building a 200-ton annual capacity gold refinery aimed at retaining more value from its exports and reducing reliance on foreign processors. And in Uganda, the inauguration of its first large-scale gold mine with associated refining capacity signals a shift toward processing and value addition onshore rather than exporting unrefined output.

These initiatives reflect a broader continental trend toward the domestication of gold value chains and the financialization of the sector.

If successfully implemented, the proposed African Gold Bank would, for the first time, attempt to connect these fragmented national efforts into a shared financial infrastructure.

For countries struggling with foreign-exchange shortages or high external vulnerability, the ability to mobilise gold domestically could become a meaningful policy tool — though not a substitute for fiscal discipline or credible monetary frameworks.

Still early, and not without risk

The project remains at a feasibility stage, and significant hurdles lie ahead. Regulatory harmonisation, governance standards, pricing transparency and liquidity management will d determine whether a Gold Bank strengthens financial stability or simply relocates existing bottlenecks.

There is also the question of scale. Gold can complement reserves, but it cannot single-handedly solve Africa’s structural FX constraints or financing gaps. Over-reliance would introduce its own risks, particularly in the event of sharp commodity-price swings.

For now, the MoU signals intent rather than execution.

Why this matters now

The timing is notable. After years of inflation shocks, FX stress and aggressive tightening, African policymakers are increasingly focused on resilience, not just growth. Reserve composition, value retention and monetary sovereignty are moving higher up the agenda.

Seen through that lens, the proposed African Gold Bank is less about mining and more about financial architecture — an attempt to rewire how Africa’s resources support its currencies, balance sheets and long-term stability.

Whether it succeeds will depend on execution. But the strategic logic is clear: Africa wants its gold to do more than leave its shores.