At independence on October 1, 1960, Nigeria was a modest, agriculture-driven economy valued at just $4.2 billion in current dollar terms, according to the World Bank. Cash crops such as cocoa, palm oil, and groundnuts powered export earnings and employment, while per capita income stood at $93 for a population of 45 million.

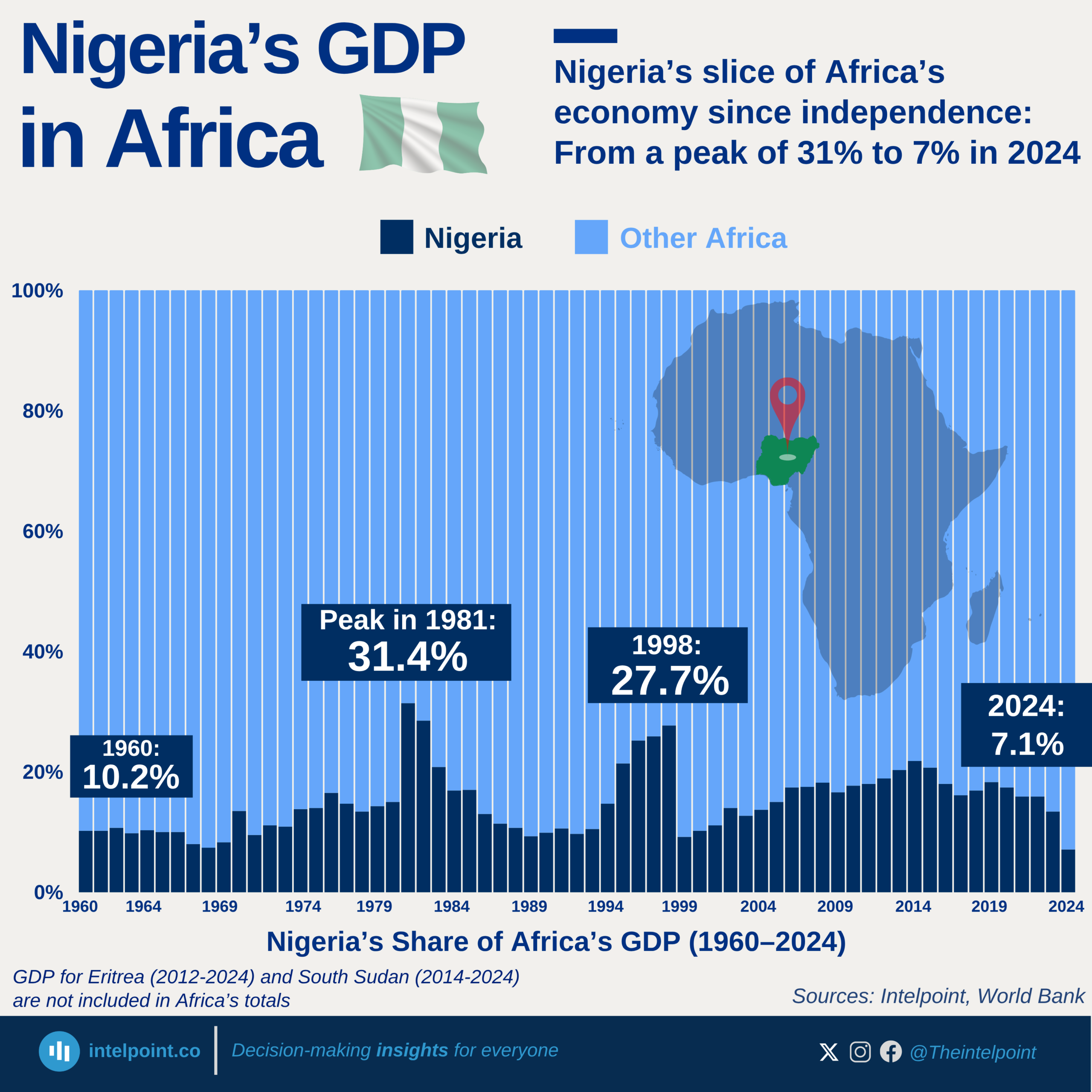

Six and a half decades later, Nigeria is Africa’s most populous nation with over 210 million people and a $250.7 billion economy. But its economic story has been defined as much by missed opportunities as by growth spurts — a cycle of oil booms, painful busts, debt crises, and reform resets.

The oil windfall and fragile foundations

The discovery of crude oil in commercial quantities in the late 1950s radically altered Nigeria’s trajectory. By 1969, oil exports accounted for 42% of total exports, and in the 1970s, they displaced agriculture as the mainstay of foreign exchange earnings.

Oil wealth strengthened the naira, which traded at near parity with the US dollar in the early 1970s. But fiscal indiscipline, over-reliance on crude, and exposure to global price shocks planted the seeds of future crises.

The 1980s collapse in oil prices plunged the economy into recession, triggered balance-of-payments pressures, and sent inflation soaring. The Structural Adjustment Programme of 1986 sought to restore stability through devaluation, trade liberalisation, and subsidy removal.

While it corrected imbalances, it also entrenched cycles of inflation and exchange-rate depreciation that continue today.

By 1999, when democracy returned, GDP growth had slowed to just 0.58%, reserves stood at $5.3 billion, and the naira had weakened to ₦69/$1.

Reform, growth, and debt relief (1999–2006)

The civilian government launched sweeping reforms in the early 2000s. Growth rebounded, averaging over 6% annually, peaking at 15.3% in 2002 amid high oil prices. Inflation fell into single digits, reserves climbed to $37.5 billion by 2006, and debt relief from the Paris Club cut external obligations by $30 billion.

Yet structural weaknesses remained. The naira continued to depreciate, reaching ₦137/$1 in 2006. The economy was still overwhelmingly dependent on crude exports.

From boom to crash (2007–2014)

The 2007–2014 period delivered solid but slowing growth. GDP expanded between 4% and 8%, reserves peaked at $58.5 billion in 2008, and inflation fluctuated in single to low double digits.

However, public debt climbed sharply, from ₦0.69 trillion ($4.59 billion) in 2010 to ₦11.2 trillion ($72.8 billion) in 2014. And the 2014 oil price crash halved Nigeria’s GDP in dollar terms, exposing once again the fragility of its oil-led model.

Recession and fragility (2015–2022)

From 2015, repeated shocks — oil price volatility, policy rigidities, and the COVID-19 pandemic — drove the economy into two recessions within five years. GDP contracted -1.62% in 2016 and -1.79% in 2020, while recoveries in 2017 and 2021 were too weak to outpace population growth.

Inflation entrenched itself in double digits, rising from 9% in 2015 to 18.8% in 2022. The naira weakened from ₦195/$1 to ₦425/$1 in the same period.

Debt exploded, rising from ₦12.6 trillion ($65.5 billion) in 2015 to ₦38.8 trillion ($91.1 billion) by 2022, as oil revenues faltered and deficits widened.

Reform, inflation, and debt surge (2023–2024)

The administration of President Bola Tinubu, which came to power in 2023, launched some of Nigeria’s boldest economic reforms in decades. Petrol subsidies were scrapped and exchange rates unified.

The moves helped correct fiscal imbalances but unleashed inflationary shocks. Inflation soared to 24.7% in 2023 and 33.2% in 2024, eroding real incomes. The naira depreciated steeply, falling to ₦1,478.9/$1 in 2024.

Debt also ballooned in naira terms, climbing from ₦97.3 trillion ($150.8 billion) in 2023 to ₦134.3 trillion ($90.8 billion) in 2024 — the steepest annual increase in Nigeria’s history.

Nigeria at 65: Gains and strains

By the second quarter of 2025, Nigeria’s rebased GDP stood at $250.7 billion, with a per capita income of $835. Growth was relatively strong at 4.23%, while inflation eased to 20.1% in August — its lowest in three years but still among the highest in Africa.

Debt reached $97.2 billion (₦149.39 trillion), though debt-to-GDP ratios looked more manageable after the rebasing.

Speaking during the 65th Independence Day nationwide broadcast on Wednesday, President Bola Tinubu highlighted what he called “tangible results” from reforms, noting a sharp rebound in non-oil revenue.

“Nigeria raised ₦3.65 trillion ($2.47 billion) in non-oil revenue in September 2025 alone, 411% higher than in May 2023,” he said. “Our debt service-to-revenue ratio has been reduced from 97% to below 50%. We have paid down the infamous ‘Ways and Means’ advances that threatened our economic stability and triggered inflation.”

The president pointed to rising tax revenues, a stronger reserve position at $42.03 billion, five consecutive quarters of trade surpluses, and a stock market rally that lifted the All-Share Index from 55,000 in May 2023 to 142,000 in September 2025.

Yet analysts caution that challenges remain. CSL Stockbrokers forecast 3.7% GDP growth for 2025, citing gains in the oil sector but warning of persistent risks from inflation and weak productivity.

Muda Yusuf, CEO of the Centre for the Promotion of Private Enterprise, noted: “Nigeria’s economic history at 65 is one of resilience, missed opportunities, and enormous untapped potential. The current reform agenda presents a rare opportunity to reset the economy, but success depends on consistent policies, stronger institutions, and making growth inclusive.”

Structural lessons

Nigeria’s 65-year journey offers sobering lessons:

- Boom-and-bust cycles: Oil-driven windfalls in the 1970s, early 2000s, and 2010s were followed by painful crashes.

- Inflation persistence: Since the 1980s, inflation has rarely dipped below double digits.

- Currency weakness: The naira has slid from 66 kobo/$1 in 1973 to nearly ₦1,500/$1 today.

- Debt burdens: From just $47.6 million in 1960, public debt has ballooned to $97.2 billion as of Q1 2025.

- Demographic pressures: Population has grown from 45 million in 1960 to over 210 million, demanding millions of jobs each year to avert widespread underemployment.

The path ahead

The key priority is sustaining disinflation and stabilising the currency. Analysts argue that the Central Bank of Nigeria must keep real interest rates positive while enhancing transparency in foreign exchange management.

Oil production — now at 1.68 million barrels per day — must be maintained to buy fiscal space, while non-oil revenues need to deepen through a broader tax base.

Social protection will be vital to shield the most vulnerable from subsidy removal and inflation shocks. And productivity growth in agriculture, industry, and services remains the only durable path to shared prosperity.

As Nigeria marks 65 years of independence, the central question is whether it can finally break free of short-lived growth spurts followed by deep reversals.

“If subsidy reform, FX unification, and fiscal tightening are matched by genuine productivity growth, diversification, and stronger governance, Nigeria at 70 could look very different,” Yusuf said. “If not, the familiar rhythm of booms and busts will continue to define Africa’s largest economy.”