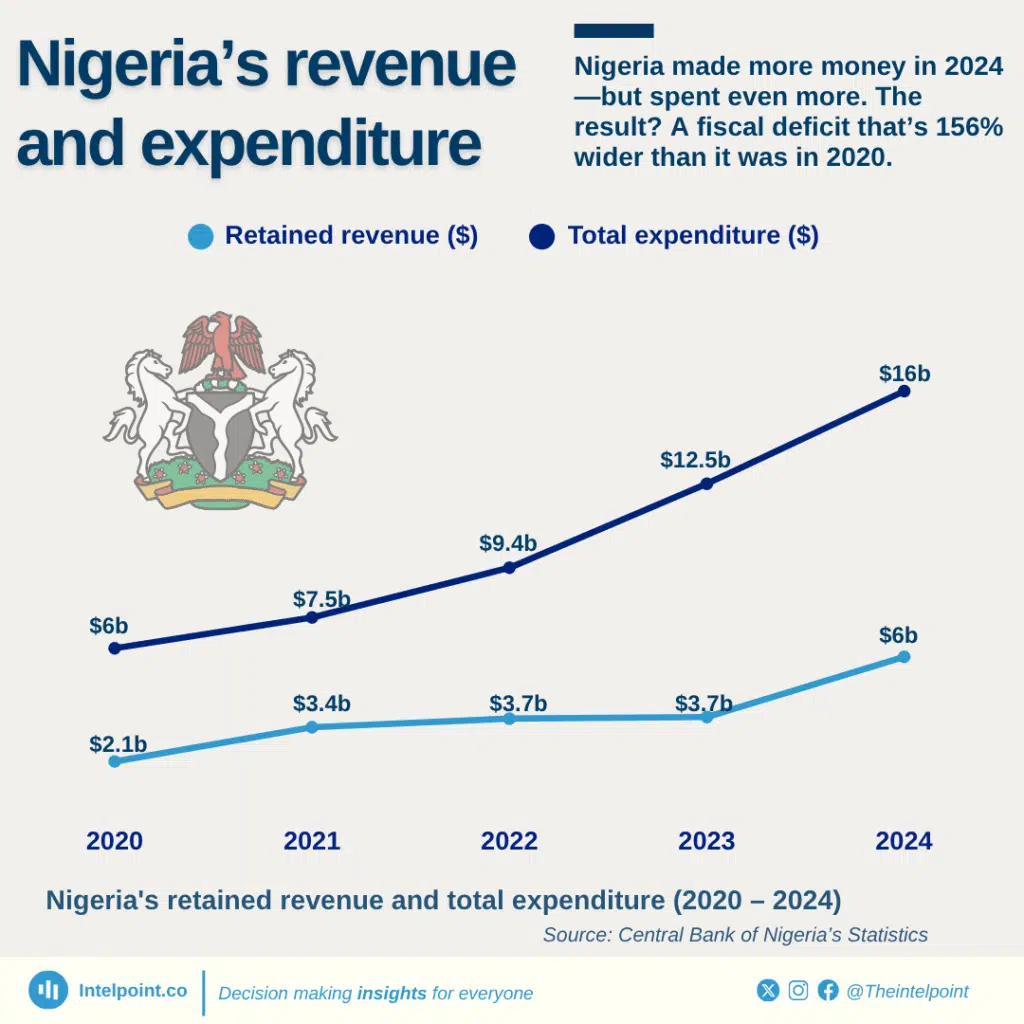

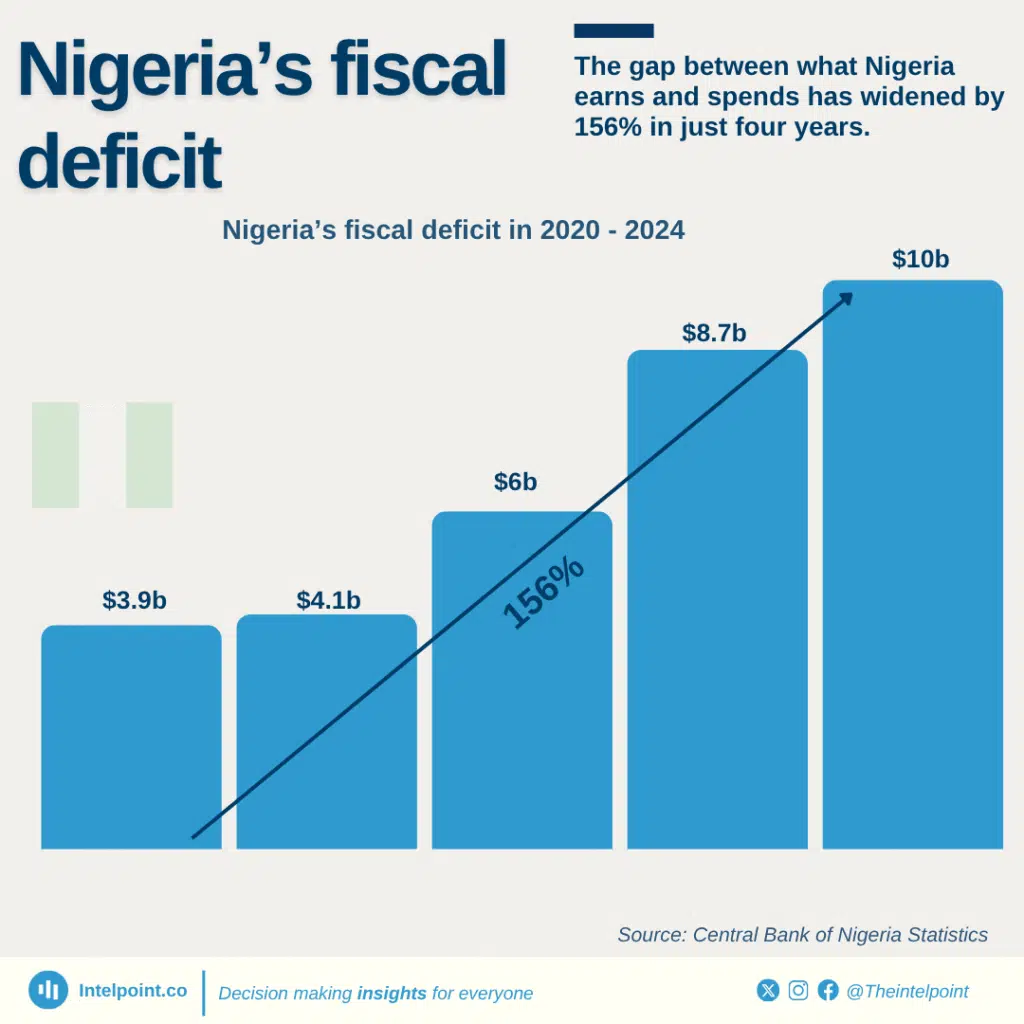

New data from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) paints a concerning picture of Nigeria’s fiscal health, revealing a federal government fiscal deficit of $9.8 billion in 2024, more than double the $4.2 billion figure reported by the Ministry of Finance just weeks earlier.

Finance Minister Wale Edun had in April presented a more optimistic scenario during an investor briefing on the sidelines of the IMF/World Bank Spring Meetings in Washington, emphasising fiscal consolidation driven by a $5 billion year-on-year increase in retained revenue to $13 billion by year-end.

According to the ministry, total expenditure reached $17.2 billion, resulting in a fiscal deficit of $4.2 billion, well below the $6 billion budget projection and representing just 2.1% of nominal GDP.

This, Edun argued, was a marked improvement compared with earlier projections and the Fiscal Responsibility Act’s 3% deficit target.

However, the CBN’s latest quarterly statistical bulletin tells a different story.

It reports a retained revenue figure of only $5.9 billion—some 55% lower than the ministry’s claims—and total expenditure of $15.6 billion, implying a fiscal deficit of $9.8 billion or 5.6% of GDP.

This figure notably exceeds the International Monetary Fund’s 4.5% deficit forecast and raises serious questions about the credibility of official fiscal data.

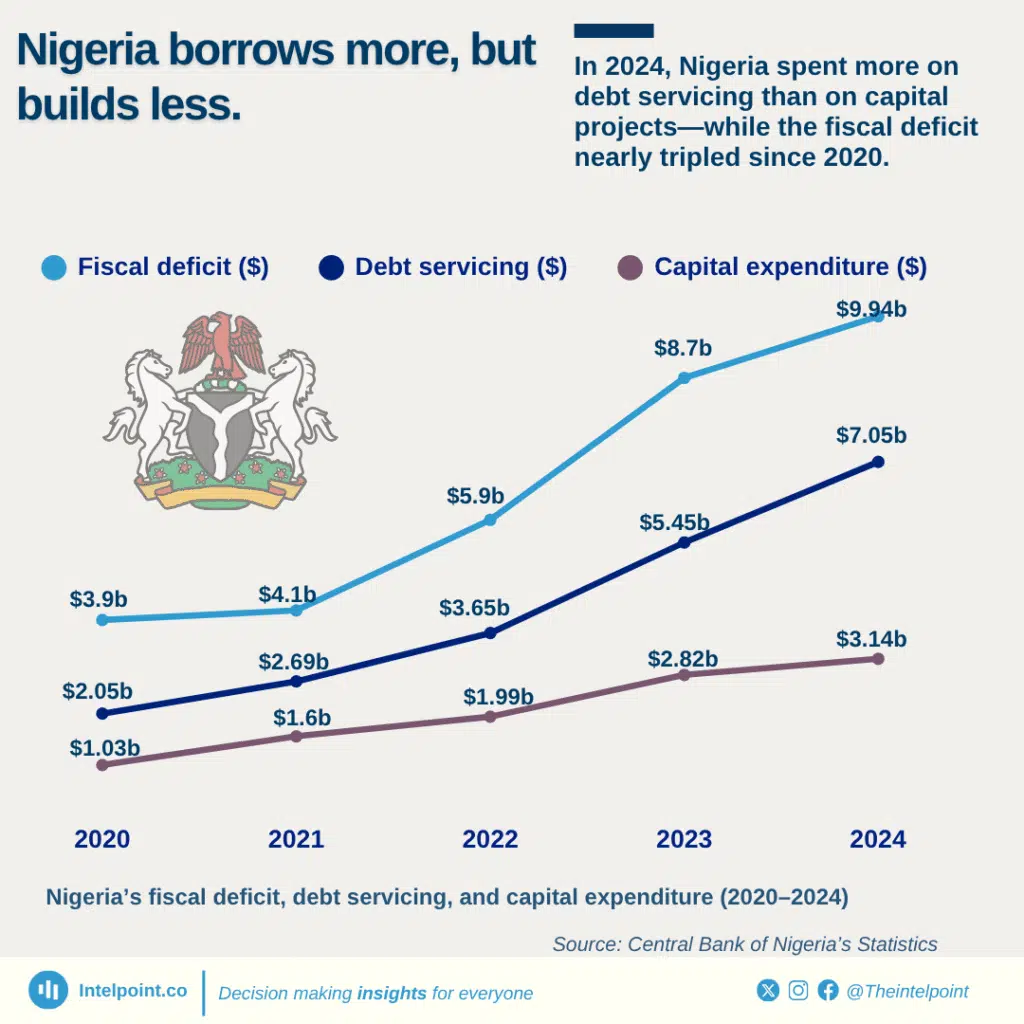

What makes the situation more alarming is the size of debt servicing costs, which the CBN estimates at approximately $6.9 billion for 2024—surpassing total revenue.

During the same period, capital spending fell to $3 billion, accounting for just 9.6% of total expenditure, far below budgeted targets and highlighting the limited funds allocated for critical developmental projects.

President Tinubu’s $24 billion external loan request raises red flags

Undeterred by the widening fiscal gap, President Bola Tinubu is pressing parliament for approval to borrow an additional $24 billion as part of a 2025-2026 external borrowing plan.

This proposed loan, nearly half of Nigeria’s current external debt of $42.5 billion, is earmarked for infrastructure, agriculture, health, education, water, security, employment, and financial reforms, relying on concessional and semi-concessional financing from bilateral and multilateral sources.

If this borrowing plan proceeds, Nigeria’s total public debt will soar from $90.6 billion at end-2024 to $114 billion, pushing the debt-to-GDP ratio from 53.7% to 67.9%. Such a sharp rise could further erode investor confidence in an economy already burdened by fragile fundamentals.

Concurrently, the government seeks to raise $2.5 billion from Nigeria’s domestic debt market to strengthen foreign exchange reserves and settle long-standing pension liabilities under the Contributory Pension Scheme, dating back two decades.

Already, the country has drawn $1.5 billion in World Bank loans since the start of the year, with additional financing of up to $2.2 billion still expected.

Though the oil producer exited the IMF’s debtor list in April after clearing a $3.4 billion Covid-19 loan, it still faces annual Special Drawing Rights (SDR) charges of roughly $30 million, adding to the mounting debt servicing burden.

In response to backlash from the latest loan proposal, the government has clarified that the $24 billion borrowing request is not new but already incorporated in the Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) for 2025 and 2026, covering borrowing plans for all 36 states and the federal government.

Yet, financial analysts dispute this claim, highlighting discrepancies with MTEF figures, which estimate total borrowing over the two-year period at just $5 billion, far below the requested amount.

“This is wrong,” says renowned financial strategist Kalu Aja. “The MTEF lists only N8 trillion ($5 million) as projected borrowing, but the letters are seeking approval for nearly N45 trillion ($25 billion) in new borrowing to be added to the debt.”

Aja argues that while borrowing isn’t inherently problematic, the funds must be directed towards productive capital projects and secured at sustainable interest rates to drive economic growth.

“Nothing wrong with debt, deficits or borrowing. I would argue Nigeria needs to borrow $1 trillion for infrastructure,” he notes.

Also read: IMF $1.8bn freeze drags on, pushing Senegal deeper into regional debt

Emphasising the crucial importance of borrowing terms, Kalu urged government officials to address the following questions before securing a new loan: “What are the interest rates on these foreign exchange borrowings? What are the projects to be executed with this debt? How will the debt of $21.5 billion, €2.2 billion, and 15 billion Japanese yen be repaid?”

Fiscal outlook: Data discrepancies test reform optimism

Back in November, the Nigerian government announced it was saving an estimated $7.5 billion annually following the removal of its longstanding fuel subsidy in 2023—a move hailed as a major fiscal reform.

The policy shift has drawn praise from international observers, including credit rating agencies like Fitch, which view it as evidence of Nigeria’s shift toward more orthodox economic management. But the recent push for a fresh $24 billion loan is now prompting questions over whether the fiscal gains from subsidy removal are being eroded by rising debt and continued budget shortfalls.

In April, Fitch upgraded Nigeria’s credit outlook from stable to positive, raising the country’s long-term foreign currency rating to B. The agency cited improved policy credibility and reduced short-term risks to economic stability.

“The upgrade reflects increased confidence in the government’s broad commitment to policy reforms implemented since its move to orthodox economic policies in June 2023, including exchange rate liberalisation, monetary policy tightening and steps to end deficit monetisation and remove fuel subsidies,” Fitch noted in its release.

Yet, the fiscal picture painted by the Central Bank of Nigeria raises doubts over the timing and durability of this positive rating action.

The scale of the deficit, combined with the high cost of debt servicing and shrinking capital expenditure, suggests that the underlying structural issues remain largely unresolved.

Beyond the data, the macroeconomic response to the reforms appears muted.

The harmonisation of exchange rate windows has introduced a unified market rate, but the naira is still projected to weaken by 6% over the next two years, according to the African Development Bank—underscoring persistent pressure on Nigeria’s external position.

Inflation also remains stubbornly high, with headline inflation at 23.7% as of April 2025 despite the central bank’s aggressive tightening cycle.

This combination of slow disinflation, weak currency expectations, and high debt servicing costs continues to test the credibility of Nigeria’s reform agenda in the eyes of investors and lenders alike.

Reform must now confront structural realities

To deliver lasting results, President Tinubu’s economic reforms must now tackle the deeper structural bottlenecks holding back Nigeria’s economy, analysts say.

Chief among these is insecurity in food-producing regions, which continues to weigh on agriculture, pushing up inflation and joblessness.

According to Aja agriculture plays a central role in driving down consumer prices in Nigeria.

He believes inflation, which has fallen by 10% in the past one year, must be brought down to around 15% to ease pressure on households and create space for productive investment.

Beyond inflation, Aja stresses the urgency of addressing Nigeria’s chronic power supply issues.

Without reliable and affordable electricity, he warns, the economy will struggle to attract the investment needed to grow industries and boost exports. “Nigeria is going nowhere without a constant affordable power supply,” he says.

He also emphasised the need to prioritise long-term development over short-term political considerations.

Note: The figures were originally reported in naira but have been converted using the exchange rate of ₦1,540 per dollar as of June 10, 2025, to aid understanding for foreign audiences