The World Bank has urged Zimbabwe to stop trying to resolve its long-running debt crisis on its own and instead work with the Group of 20 (G20) nations to secure a coordinated solution under the Common Framework.

Speaking in an interview with Bloomberg on Monday in Mozambique, Ajay Banga, the Bank’s president said that the country stood a better chance of breaking out of its debt trap if it participated in a multilateral process.

“Trying to figure it out on your own, you’ll be doing this for the next five years,” said Banga. “They need to figure out a way to reach out to the G-20 and say, we raise our hand, we’d like to be part of this process.”

Zimbabwe, which owes $21 billion to the Washington-based lender and other creditors , has been locked out of global capital markets since 2000, when it first defaulted on its debt.

Over the years, authorities have made repeated, but unsuccessful, attempts to restore creditworthiness, including plans to repay debt with mineral proceeds and recent efforts to raise $2.6 billion from ten partner countries to clear arrears.

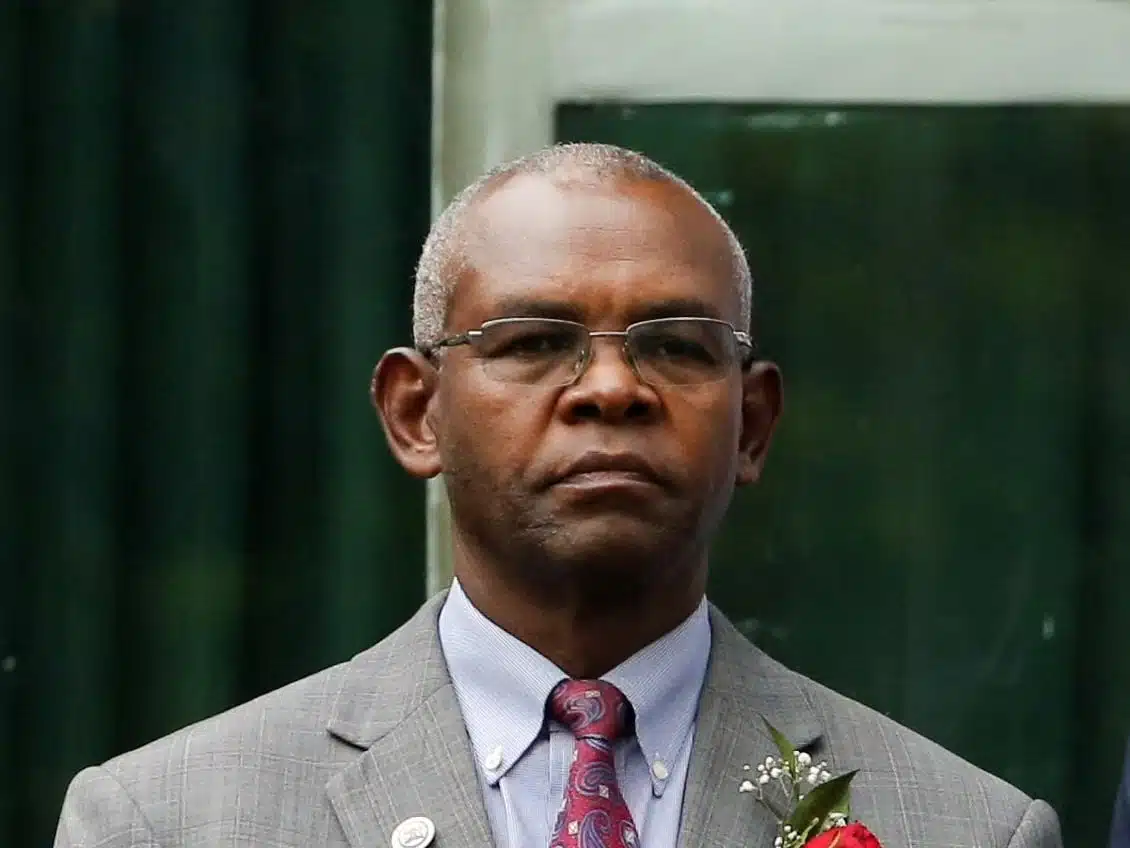

The government has also turned to the African Development Bank (AfDB) for technical support, appointing outgoing AfDB President Akinwumi Adesina and former Mozambican President Joaquim Chissano to lead creditor talks.

It further enlisted the services of Global Sovereign Advisory, a Paris-based consultancy. However, the process has been complicated by US sanctions against senior Zimbabwean officials, including President Emmerson Mnangagwa.

While many other countries remain in arrears with the World Bank, Zimbabwe’s default is the longest-running. Last month, South Africa, the current holder of the G20 presidency, confirmed that it had been approached by Zimbabwe to help secure the group’s support for a debt workout.

Common Framework in focus

The G20 Common Framework was established to assist heavily indebted low-income countries in coordinating debt restructuring across official and private creditors.

Ghana and Zambia are among African countries already engaged under the mechanism. Zambia, which defaulted in 2020, has secured agreements for around 90% of the debt being restructured.

Although critical deals with the Export-Import Bank of China and two regional lenders are still pending. The delays have created uncertainty for a country still recovering from last year’s El-Ninõ-triggered drought and facing broader fiscal pressures.

In Ghana’s case, authorities recently announced the repayment of $700 million to Eurobond holders, reducing the country’s total debt from $69.8 billion at the end of 2024 to $58.9 billion by June 2025.

As a result, the percentage of debt to Gross domestic product fell to 43.8%, reflecting progress under its own restructuring process launched after defaulting in 2022.

Zimbabwe, by contrast, continues to explore piecemeal options. But for Banga and other market observers, the time has come for a more structured approach.